This text begins with the geopolitical metaphor of the octopus. An animal with long tentacles that allow it to move, adapt to numerous surfaces and conditions, and capture prey for food. In the geopolitical sphere, the octopus was used to refer to the United Fruit Company (UFCO) or the US banana «sector»—characterized by its monopoly. I revisit this metaphor to discuss how Donald Trump seeks to consolidate the US presence in the region and enhance its capacity for interference in our countries.

Geopolitical Configuration of Central America

Geographically, the region refers to a landmass that unites North and South America, making it a biodiverse and cultural bridge where both extremes meet. With the imposition of colonialism, Central America was configured as a transisthmian territory that had to be crossed to guarantee extra-regional connectivity—an entirely colonial necessity. This situation equated the region with the Caribbean, as the European gateway to the Pacific or the entrance to Europe, from the American perspective. It was amidst this transisthmian tension that the notion of the geopolitical Caribbean was coined to refer to the territories bordering the Caribbean Sea: the Caribbean islands, Central America, and Panama.

Once the interests were clear, different routes were proposed for building an interoceanic canal: there were attempts to do so across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, or along the banks of the San Juan River on the border between Nicaragua and Costa Rica, and finally in Panamanian territory. This last route, however, sparked tensions between the nascent United States and the British Crown. Therefore, it is not surprising that for Alfred T. Mahan (admiral and geopolitical thinker who influenced American geopolitics), strengthening naval power was key to guaranteeing the security and survival of the United States against a predominantly maritime empire—Great Britain. Mahan also fueled the Monroe Doctrine by portraying the Panama Canal as an existential project for the nascent North American power.

According to journalist Florian Louis, it was in 1823 that President James Monroe delivered the speech that shaped what we know today as the Monroe Doctrine. At that time, the United States was still a young country, with far less territory and common resources to exploit—hydrocarbons. In his words, the president committed his nation to pushing back the presence of extra-continental imperialisms, thus making the U.S. a kind of “guarantor” of American independence. This is a problematic and ambiguous issue in itself, as it refers only to an external enemy as if imperialist ambitions did not exist on the continent.

The geopolitical tension surrounding the interoceanic canal led to Theodore Roosevelt’s reinterpretation of the Monroe Doctrine: the U.S. has the unilateral right to intervene in foreign territories to protect its security and interests. According to researcher Elisa Gómez, the justification for intervention was the “incapacity of Latin American and Caribbean countries to govern themselves and their lack of responsibility for their international commitments.” Commitments that must be interpreted in light of U.S. interests, not national or independent ones.

After numerous tensions, the “America for the Americans” and Pax Americana prevailed: the zone—surrounding territories—and the canal are U.S. projects. Thus, Central America was completely reshaped: Panama was assimilated into the canal, Nicaragua was militarily occupied for decades, and Costa Rica and Honduras were consolidated as military/political bases that functioned during the counterinsurgency war. This would make Central America and the Caribbean “one of the most important regions in the world,” in the words of Jeane Kirkpatrick (Republican ideologue and ambassador to the United Nations during the Ronald Reagan administration). In the sense that the security of Central America also depends on the rearguard of the naval base at Guantanamo and the canal. The latter also controls communication between the US coasts, the gateway to Europe, and the barrier behind the Caribbean—»our sea,» as US geopoliticians call the Caribbean, Mexico, Central America, Colombia, and Venezuela. Thus, the geopolitical value of Central America refers to the capacity for movement, displacement, and the point of supply for military personnel or basic necessities in times of conflict. This is no small matter.

The Octopus, the Banana Republic as Imperialist Logic

According to Fernanda Zeledón (2022), the presence of the banana agro-industry in Central America dates back to 1899; several decades after the establishment of the Monroe Doctrine and amidst the political disputes surrounding the canal—built in 1904 and inaugurated 10 years later—were a key factor in the development of the industry. This industry was preceded by agreements with the governments of the newly formed Central American countries, which promoted land concessions in exchange for infrastructure construction or transportation development. These agreements aimed to satisfy the state’s need to expand territorial control and infrastructure, thereby enabling industrial development.

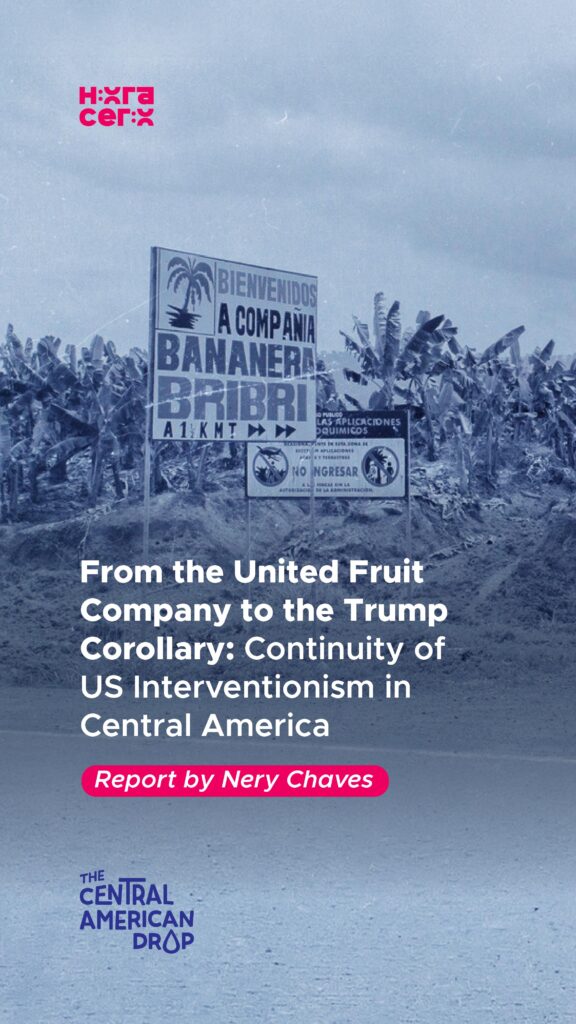

The octopus serves as a fairly accurate metaphor for the impact of the United Fruit Company (UFCO) and the Standard Fruit Company in Central America and Colombia. It was an image created to illustrate an industry that, by 1930, controlled 1,409,148 hectares of land in the region (according to Zeledón). UFCO managed to monopolize banana exports from Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, and Panama. But this monopoly extended beyond agribusiness and encompassed, at the very least, the transportation, communication, and road infrastructure connecting various strategic points—the ports for export—and the control of everything that happened within the plantations. This control ranged from grocery stores for the workers to the maintenance of extremely precarious working conditions, bordering on slavery (for example, banana plantation workers received vouchers in exchange for their labor that could only be used in company stores). Therefore, it is not surprising that the banana plantations were also a breeding ground for union organizing and labor movements that would be labeled as agitators or communists.

In this sense, the specialized literature affirms that an enclave economic system existed in the banana plantations: vast tracts of land under the administration of a transnational corporation that provided no benefit to the host country. In practice, a corporate state operated—extrajudicially—within another state, with no other condition than the construction of transportation infrastructure. Thus, the notion of an octopus takes on greater dimensions, as the UFCO went beyond being an agribusiness company, seeking to monopolize all social, economic, and political aspects within the plantations and surrounding territories. This is because most of the land granted to the UFCO was not cultivated but rather «available» to the company in case any land became depleted—banana monoculture quickly damages the soil or the plants, leading to a high degree of displacement—or to prevent its use by competitors. In this sense, the accumulation of land had the sole purpose of displacing everything: entire communities and the State itself.

Fernanda Zeledón argues that the UFCO’s success depended on its support for authoritarian governments and leaders. For example, its role was key—though not the only one—in the overthrow of Jacobo Arbenz in Guatemala (due to his proposed agrarian reform that would expropriate uncultivated land from the banana company) in 1954, and much earlier (1910) it had supported Manuel Bonilla in his attempt to regain power in Honduras. In this sense, the UFCO was aligned with US interests in the region, with the propagation of the National Security Doctrine (NSD)—following the triumph of the Cuban Revolution—and its strengthening after the arrival of the Sandinista Revolution in Nicaragua in 1979.

Andrés León, a Costa Rican researcher, argues that the Central American military governments, with US support, constructed an “imperial solidarity” by identifying security as “the point of convergence between the processes of Central American state formation and US imperial formation.” Imperial solidarity that entailed coups d’état and the globalization of public violence as a structural condition of the region.

Transformation of the Octopus

One of the keys to the banana industry’s success, in the words of researcher Philippe Burgois, was its capacity for adaptation and transformation. This capacity was possible thanks to its mobility and influence among the territories and governments in power: the enclave imposed Central American economies that were highly dependent on and vulnerable to international market conditions, with structural weaknesses that persist to this day. Evidently, this condition extended to the political sphere and to the imperial solidarity built by the military governments and transferred to the democracies established after the peace accords.

Central America was secured, but peace never arrived; on the contrary, security has been a pillar of relations with the U.S. Within this framework, drug trafficking has been a central element in the invasion and overthrow of Noriega in Panama, and the extradition, conviction, and subsequent release of Juan Orlando Hernández (JOH), the former president of Honduras.

| Cookie | Duración | Descripción |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |