“You are the United States,

You are the future invader

of the naive America that has indigenous blood,

who still prays to Jesus Christ and still speaks Spanish.”

Rubén Darío, Ode to Roosevelt (1912)

Central America, within the context of the US imperial world, has been a laboratory and a school for the United States. To understand its interference, one must look at the territory and comprehend the impact not only of military interventions, the construction of military bases, or its involvement in coups and support for dictatorships, but also of the way in which US power— political, economic, and military— has organized the region’s space, crops, seas, and even forests.

This is not a new phenomenon, says Pascal Girot, director of the School of Geography at the University of Costa Rica. According to the academic, the history of U.S. interference in the region begins, at least, with the presence of Cornelius Vanderbilt and William Walker in the mid-19th century, when «the Americans sought to expand their plantations and maintain slavery in much of the region.»

This logic deepened with the banana boom and an “enclave” model. From Minor Keith, with the railway industry and the founding of United Fruit Company, through its successor Chiquita Brands that dominated the banana industry in Central America and the Caribbean, were creating, in Girot’s words, «States within the State».

“Within the banana plantations, there was almost a government where the Costa Rican, Honduran, and Guatemalan states ceded a good part of the activities of police control, taxation, and other functions proper to the national state. The same was true of the Panama Canal enclave, where there was a government, a Canal commission,” he explains.

It was more than a century of enclaves accompanied by open armed interventions and support for coups d’état. Environmentally, this translates into successive cycles of extractivism: bananas, extensive cattle ranching, African palm, pineapple, mining, hydrocarbons, megaprojects, infrastructure, energy, and, in some cases, Bitcoin and nuclear power. In this article, we will examine five key elements that contribute to understanding the environmental, extractivist, and colonialist impacts of the United States in Central America.

The Panama Canal

The United States’ footprint in this country encapsulates the link between geopolitics and ecology from the colonialist perspective of the northern nation. Raisa Banfield, director of the Panama Foundation, describes it as a «love-hate» relationship: «That is, I love you, we are brothers, we help each other, but I get ‘overwhelmed’ and I break off relations with you, and somehow you still have a strong presence.»

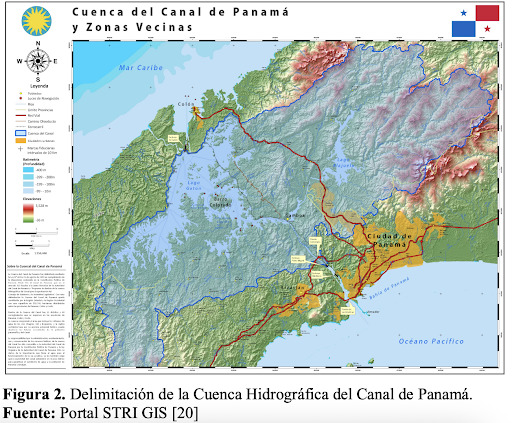

The construction and subsequent expansion of the Panama Canal, promoted and controlled by the United States for decades. These projects radically transformed the ecosystems of the isthmus region. The opening of dams, sluices, and artificial lakes led to the flooding of vast areas of tropical forest, the fragmentation of habitats, and the permanent alteration of water flows, with cumulative impacts on biodiversity, soils, and hydrological cycles.

This is compounded by the deforestation of the canal basin. Some research, such as that conducted by the Technological University of Panama warn that the loss of forest increases the risks of soil erosion and sediment runoff into the Canal, compromising the quality and quantity of water available for both the operation of the waterway and the communities, and increasing the vulnerability of the area during extreme events related to Climate Change.

For Banfield, the situation is exacerbated by the development model, resource management, and human inexperience in dealing with nature. Regarding US President Donald Trump’s claim of ownership of the Panama Canal, the director reiterated that any concession cannot supersede the sovereignty of nations.

“I don’t like to use the word “recover” because they didn’t lose anything here. Simply put, history and the entire Panamanian struggle for sovereignty demonstrated what was obvious: the land is ours, the natural resources are ours. They provided the engineering, recouped their investment, period, like any concession in modern times. That doesn’t make you the owner of what has no owner, which is the right of a nation.

Raisa recalled that last January 9th marked the anniversary of Martyrs’ Day, the Torrijos-Carter Uprising, a popular student uprising that defended national sovereignty by attempting to raise the Panamanian flag in the Canal Zone in 1964, sparking massive riots and resulting in the deaths of more than 20 students. This event intensified relations with the United States, ultimately leading to the signing of the Torrijos-Carter Treaties in 1977, which eventually returned control of the Canal to Panama.

“That event reminds us that sovereignty is not something you acquire and hang on a wall forever; it is something you recognize as fragile and must defend. And we are seeing that fragility today, when Trump claims Venezuela’s oil, a natural resource geologically located in a place that does not belong to it. The same applies to the canal; it was a geopolitical decision agreed upon through the legal, diplomatic, and international law channels that govern us as nations.”

Military bases

In 1903, the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty established the Panama Canal Zone, granting the United States «perpetual rights of use, occupation, and control,» which allowed the US to build 14 military bases. This territory was later recovered by Panama through subsequent treaties. Research such as that conducted by Foreign Policy in Focus points out that the Pentagon transferred training fields and firing ranges without a complete inventory, leaving spilled fuels, acid batteries, heavy metals, and other toxic substances in soils and bodies of water that are now used by communities and are part of the canal environment.

The study also states that they have documented more than 100,000 unexploded explosive devices found in old firing ranges near the Canal. Despite agreements with the United States stipulating their removal, these war remnants remain, limiting the use of natural areas, blocking public access to projects, and posing a constant threat to human life and wildlife. Furthermore, they constrain the country’s environmental and territorial planning, which lacks complete technical information on the contaminated sites.

“We know that this was the site of rehearsals and training exercises for the Vietnam War, the Korean War, and World War II. Many unexploded ordnance remains here, and the United States still hasn’t taken responsibility for clearing the areas. Many of these unexploded ordnances are located in protected areas. The forest is untouched, but if we wanted to take advantage of this to make it more interactive for people, for ecotourism, we can’t,” said Raisa Banfield.

Currently, the United States has military bases in El Salvador and Honduras.

The dark legacy of North American agribusiness

The agro-industrial model geared towards the US market—bananas, oil palm, sugarcane, and other crops—has reshaped vast tracts of land in countries like Guatemala and Honduras, under the influence of companies historically linked to North American capital, such as the former United Fruit Company and its subsidiaries, and currently, large agro-industrial conglomerates like The Cargill Group with a presence throughout Central America

In the case of oil palm and other monocultures, community testimonies and studies such as the one carried out by Dr. Steve Marquardt, director of the Center for Labor Studies at the University of Washington, have pointed out the direct contamination of waterways by industrial and agrochemical runoff, with the death of aquatic fauna and the loss of clean water sources for rural populations.

To achieve high yields, these agro-industrial complexes require large continuous areas of land, which has favored the deforestation of primary forests and wetlands in the Central American region.

Research from the University of Washington shows that the corporate response to pests that affected banana plantations was to drain, flood, or transform thousands of hectares of tropical forest into highly intervened agricultural systems, altering soils, hydrology, and landscapes according to an export system dominated by demand and chains in the United States.

“I believe these human and environmental tragedies have deep historical roots. Some of those roots are buried in soils infected by Panama disease,” Marquardt concludes.

Forests vs. the meat industry in Nicaragua

In 2024, Nicaragua lost 144 square hectares of natural forest, equivalent to 81.0 Mt of CO₂ emissions. Its average annual deforestation rate is high at 5.8%. Between 2023 and 2024, the situation accelerated due, among other factors, to the expansion of livestock farming and the allocation of land for megaprojects. According to the portal exportgenius, Nicaragua exports approximately $361 million worth of meat to the United States, one of the Central American country’s main export partners. Meanwhile, as of 2022, 50% of the country’s land area was dedicated to pastureland for livestock. In 2024, Nicaragua had the highest rate of deforestation in the entire region. The World Resources Institute (WRI) ranks it among the top 10 countries with the greatest loss of primary forests.

In this context, the beef that various distributors export from Nicaragua to companies like Burger King, Applebee’s, Chili’s, Walmart, and others is linked to illegal logging, the violent dispossession of Indigenous lands, human rights violations, and environmental destruction. This was revealed in a new report, an investigation into the “Patrol” campaign, filmmakers of the documentary of the same name that addresses the topic and is supported by the organization Re:Wild.

The documentary «Patrol» tells the story of Indigenous rangers working to address threats to the Rama Kriol Indigenous Territory. «This isn’t just a problem in Nicaragua; it’s a failure in the global supply chain. Solving it will require urgent action from governments, businesses, and consumers alike,» said Camilo de Castro, the documentary’s author.

The report, published in October 2025, focuses specifically on cattle that originate from cattle farms in two indigenous territories of Nicaragua: the Mayangna Sauni Bas Territory in the Bosawas Biosphere Reserve, declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO and one of the most biodiverse ecosystems on the planet, and the Rama and Kriol Indigenous Territory, located within the boundaries of the Indio Maíz Biological Reserve, one of the Five Great Forests of Mesoamerica and a Key Biodiversity Area.

The new trade agreements with El Salvador and Guatemala

These reciprocal trade agreements signed between the United States and El Salvador and Guatemala deepen the opening of the agribusiness, technology industry, and extractive mining to the US market.

Both countries must accept, without objection, US criteria, products, and standards, and cannot establish trade relations with other countries that the United States considers to «compromise its national security,» in addition to not imposing taxes that «discriminate against companies» from this country.

Although the texts include environmental protection clauses and references to combating crimes against nature, such as illegal logging, illegal wildlife trafficking, illegal mining, and managing sustainable fishing, they also consolidate a legal framework that allows for increased exports of agricultural and natural resources to the United States in contexts where environmental protection institutions are weak in the face of environmental crimes.

For example, Guatemalan legislation allows companies to settle cases of environmental crimes, such as dumping waste into a lake for $13,000 or contaminating soil with toxic metals for $40,000, opening the door for them to avoid prosecution for environmental offenses. In El Salvador, serious setbacks are being faced, such as the approval of metallic mining and an increase in the criminalization of land defenders.

Both Raisa and Pascal emphasize the importance of looking back at Central American history to develop strategies to counter the interventionism and environmental, social, and economic impacts of powers like the United States. “We need to learn that to coexist in this world, we have to learn to coexist with our planet,” Raisa stated.

Pascal, for his part, believes that, despite the context of global crisis, a strategy of resistance and survival is to bet on cooperativism, family farming, and the solidarity of the communities and peoples of the region in the face of the handover of territories to the great powers.

“The United States is a ‘big monster with heavy footsteps.’ It comes with very strong interests and unprecedented means to subjugate and overwhelm Central American economies and populations. Defending our territory and food sovereignty is crucial.”

| Cookie | Duración | Descripción |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |