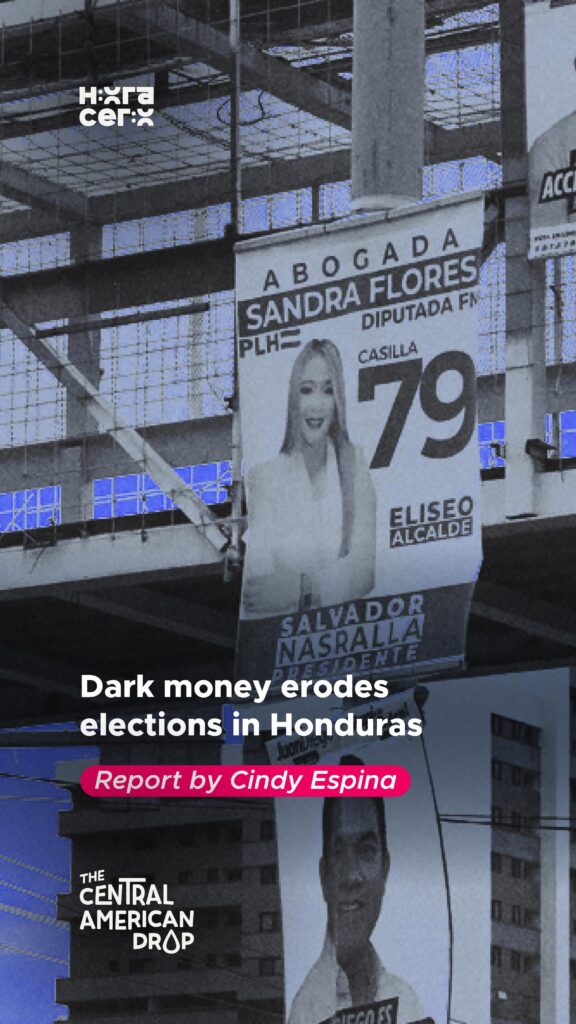

Dark money erodes elections in Honduras

Maldito País

octubre 8, 2025

By Osiris Payes

My request for information from the Political Parties and Candidates Financing, Transparency, and Oversight Unit (UFTF) was denied. I requested public data on candidates running in the general elections who failed to submit their financial reports. The official response was that the documents were «under development» and would be published later. This evasive response, reflected in memorandum SG-UFTF-209-20251, is evidence of how opacity is normalized in an institution that, in theory, should be the most transparent with political financing.

Politics costs money. Parties need it to organize events, mobilize voters, commission polls, print materials, and appear on television. This triggers the flow of resources from private interests, and some least desired funds from the State, drug trafficking, and organized crime. Ideally, contributions should be governed by clear rules and subject to public scrutiny.

However, in Honduras, worrying examples abound. Regarding the finances of the National Party, trials in the United States revealed that former President Juan Orlando Hernández received funds from drug trafficking, including a million dollars delivered by «El Chapo» Guzmán through his brother Tony, convicted of drug trafficking in New York 2.

In the Liberal Party, the case of Yani Rosenthal exposed how organized crime funds were used to finance political activities. Rosenthal was convicted in the U.S. for laundering money for the Los Cachiros cartel, revealing how these criminal networks permeated party structures 3.

In the Liberty and Refoundation Party (Libre), the so-called «narco-video» of 2013 showed Congressman Carlos Zelaya Rosales, brother-in-law of the current president, meeting with alleged drug traffickers to negotiate campaign financing of millions of lempiras 4.

These cases are joined by others similar in modus operandi, such as Pandora (2013) 5 and Sedesol’s Checazo 6 (2025), which document how funds are diverted from public coffers to illegally finance campaigns.

These episodes illustrate a pattern among the three major parties and their connection to the use of funds from drug trafficking, organized crime, and the state. Money becomes a determining factor not only for competition but also for winning support. As authors Grossman and Helpman warn, these contributions skew the parties’ positions and bias the results, pushing them away from the public interest.

The Honduran legal framework establishes electoral spending limits, with differentiated limits for elected offices. On paper, this regulation is intended to balance competition. In practice, however, these controls are fictitious. Financial reports are not submitted or published, and parties act as if compliance were optional. In the most recent primary elections, 47% of candidates did not even open a bank account to channel funds 7, despite it being a basic requirement. When three out of six candidates openly fail to comply, the legal limits are reduced to paper.

This failure is rooted in what we might call the architecture of opacity. Information Confidentiality Agreement 001-2018 (on which the Center for Democracy Studies filed a constitutional appeal and which has already been accepted), requested by the UFTF and validated by the Institute for Access to Public Information (IAIP), shielded key data on funding: donor names, amounts, and audits 8. The reserve remains in effect, consolidating the partisan capture of the entity that should guarantee transparency. Added to this are decisions by Congress, such as Decree 94-2021 and its extensions, which relaxed the sanctioning regime and reduced the scope of fines, sending a message that there are no real consequences for those who fail to comply.

Recent events confirm this trend. The UFTF itself acknowledged that 85 elected pre-candidates failed to submit their financial reports and announced that it would send the files to the Attorney General’s Office for penalties. However, when citizens request to know who these delinquents are, which parties are most in breach, and the status of the files, the response is a tacit refusal, with generic expressions based on the argument that the reports «are being prepared.» This not only lacks legal basis (the Transparency Law requires a response within a maximum of ten business days, with only one justified extension), but it also normalizes secrecy where accountability should prevail.

Without verifiable information, spending limits and oversight lose their effectiveness. Electoral competition is not decided on a level playing field, but rather under the shadow of dark money. Democracy becomes a market of influence, where private or illicit resources define candidates and agendas, while citizens are left without any real options to elect someone who truly represents their interests.

Honduras is in a decisive electoral process, still carrying with it this legacy of reservations, evasions, and weakened sanctions. Continuing to tolerate this opacity is tantamount to accepting that political representation can be bought and that democratic trust will continue to erode. It is not enough to point out that 85 elected pre-candidates failed to submit their reports; the names, parties, and positions must be published in open formats, the files must be publicly accessible, and the sanctions regime must be truly effective.

The solution is not complicated; it depends on the UPL’s willingness to lift the confidentiality of Agreement 001-2018, publish data promptly, comply with the deadlines established by the Transparency Law, and implement effective sanctions for those who violate the regulations. These are minimal steps to enable citizens to monitor what happens with money in politics.

The press, academia, and civil society must demand compliance with the Transparency Law without exception. Financial accountability is not just an administrative procedure; it is an essential condition for elections to reflect the will of the people and not the purchasing power of a few. As long as information remains hidden, Honduran democracy will be condemned to being held hostage by interests that impose themselves with money and conceal themselves with institutional silence.

Notes:

file:///Users/opayes/Downloads/MEMORANDO%20No.%20SG-UFTF-209-2025.pdf

https://insightcrime.org/es/noticias-crimen-organizado-honduras/juan-orlando-hernandez/

https://insightcrime.org/es/noticias/noticias-del-dia/magnate-honduras-declara-culpable-lavado-dinero-estados-unidos/

https://web.facebook.com/expedientepublicohn/videos/difunden-video-de-carlos-zelaya-negociando-sobornos-con-narcos/1064459221863577/?_rdc=1&_rdr

La Caja de Pandora

https://www.elpais.hn/hallan-posibles-delitos-en-investigacion-del-checazo-en-la-secretaria-de-desarrollo-social/

https://cespad.org.hn/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Analisis-Prospectivo-VF-0604.pdf

- https://cespad.org.hn/como-la-opacidad-y-la-falta-de-rendicion-de-cuentas-siguen-obstaculizando-la-fiscalizacion-del-financiamiento-politico-en-honduras/