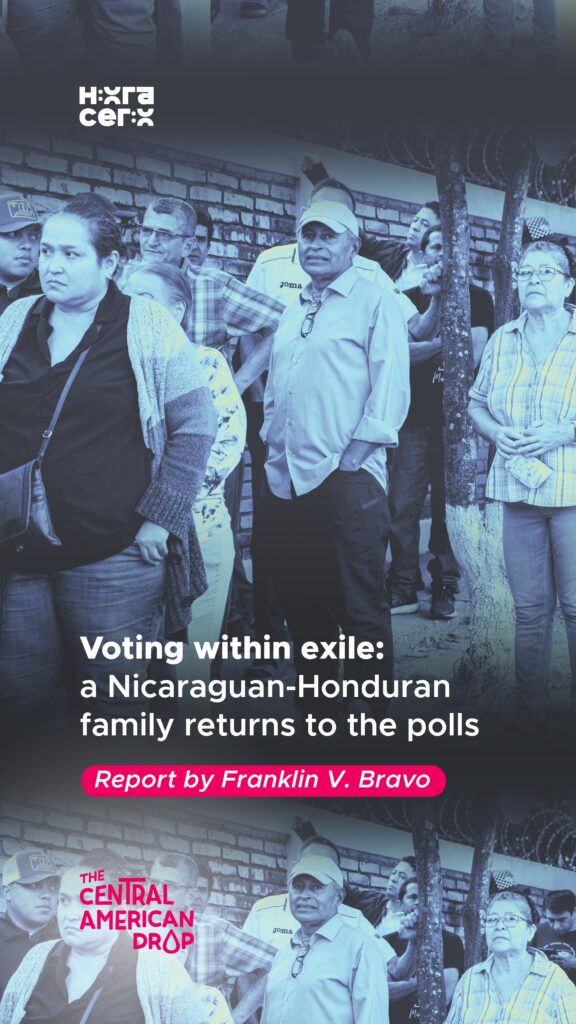

The humid heat of Honduras is usually stifling, but for Eduardo Delgado, a 21-year-old international relations student, the jacket he was wearing wasn’t a choice; it was a shield. On November 30, he was walking to his polling place in a municipality different from where he lives, a place considered a hotspot of the violence plaguing the Central American country, which that day was debating its future at the ballot box. Eduardo has tattoos, and in the unwritten codes of neighborhoods controlled by organized crime, ink on the skin can be a death sentence.

As he marched through banners and partisan fervor, what is sometimes called a “civic celebration,” Eduardo grappled with an inner tension that seemed out of place in the electoral atmosphere. It was the symbolic weight of the moment and of his own history: this would be the first time in his life that he would exercise his right to vote. However, he would not be doing so in his native Nicaragua, but in the country that opened its doors to him when his family decided to flee in 2018 because of the authoritarian regime of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo. The dictatorial couple who have plunged the country into a crisis that seems impossible to end.

For years, Eduardo felt that this moment—voting in a country that wasn’t his own—didn’t belong to him. «I appreciate the refuge, but I still don’t have that sense of belonging,» he would tell himself. But something changed after working on social projects in Cortés and witnessing firsthand the extreme poverty of one of the poorest countries in Latin America.

“It was that feeling that made me say, I have to give something back to this country. And I think the best way I can do that is through my informed and conscious vote. I think that’s the best gift I can give to this country,” he reflects in a phone call the day after the election.

That Sunday, Eduardo voted, thus sealing a chapter in his present and his binational identity. In addition to being Nicaraguan, he holds Honduran citizenship, and part of his maternal family lives there.

To understand the significance of an act that is, to some extent, commonplace, it is necessary to understand the Nicaragua of the Ortega-Murillo regime. He was only 14 years old when he left the country with his mother, Cristina Galindo. Both are Honduran through their mother’s side—Eduardo’s grandmother was from Honduras, which granted them citizenship and full political rights. But legal documents don’t erase the memory of the country where they were born and lived almost their entire lives.

Eduardo belongs to a generation that grew up watching democracy crumble. He was born in 2004, under neoliberal governments that promised democracy and progress. Nicaragua opened itself to the world, as many countries did in the 2000s, with the rise of neoliberalism and globalization, promising a more connected world. But ultimately, the strings of Nicaraguan politics weren’t driven by ideology. Pacts and acts of corruption were forged that stagnated Nicaragua and paved the way for Ortega’s eternal personalistic and authoritarian project.

When the Sandinista Front returned to power, Eduardo was three years old. He inherited a country that would collapse in less than two decades. He grew up witnessing the consolidation of an authoritarian regime and experienced his adolescence amidst tumultuous protests, repression, extrajudicial killings, and grave human rights violations. He was 14 when he went into exile.

“I have to prevent the place that welcomed me from becoming like the place I escaped from, right? But then other biases and ideologies come into play, right? And at the end of the day, I think that makes us prone to making serious mistakes when voting or supporting leader X or Y,” Eduardo reflects.

Eduardo admits he tried to separate the two realities, but the ghosts of his past cross borders. Seeing certain «dogmas» regarding the voting and ideology of some of his Honduran colleagues, Eduardo can’t help but feel bewildered. For him, politics isn’t an act of blind faith; it’s a way to reaffirm his identity and settle in the country that welcomed him. And also to contribute to shaping that country’s future.

While Eduardo was having these thoughts as he cast his first vote, Cristina Galindo was breaking more than a decade of abstention. The last time she voted was in the 2009 Nicaraguan municipal elections. Since then, the consolidation of the dictatorship and the electoral farce in her native country had kept her away from the polls.

During the previous election in Honduras, in which Xiomara Castro emerged victorious, Cristina decided to abstain. She felt caught in an ethical dilemma. She couldn’t validate the government of Juan Orlando Hernández, known for corruption and abuses, with her vote, but neither was she ready to support a left wing whose rhetoric reminded her too much of the wounds inflicted by Sandinismo in Nicaragua. «I felt very conflicted… I didn’t identify with it,» she confesses.

However, for this election, abstention was no longer a viable option. It wasn’t a political rally that mobilized her, but the direct questioning of students. «How is it possible that you’re not voting? It’s a civic right,» the young people challenged her. Cristina, who has dedicated her life to political and social education, felt the contradiction. She couldn’t promote rights that she herself refused to exercise. She decided to vote to honor her Honduran mother’s heritage and to remain consistent with a generation of young people who still believe in change.

On election day, mother and son woke up with the fears common to those who come from a failed state: fear of fraud or political violence. But what Cristina and Eduardo found in the streets was a “civic celebration,” despite everything.

Cristina reunited with her maternal family. They went to vote, had coffee, and walked through streets that, far from being a battlefield, were filled with families and people who, against all odds in a turbulent Central America, found voting to be a civic exercise. She was surprised by the normalcy of the process: a functional biometric system, orderly lines, and the absence of coercion. “It was a very enlightening experience,” she recounts, moved to see how a country with such fragile institutions and plagued by organized crime could achieve something unthinkable in Nicaragua today.

The day ended with a scene that demonstrated the anticipation of a country deciding its destiny at the ballot box. The whole family gathered in front of the television, awaiting the preliminary results.

The act of voting, however, is not a magic formula, nor is it the sole guarantee of democracy. After the euphoria of Sunday, Eduardo maintains a critical perspective. The young man is concerned that the result could bring back figures linked to drug trafficking and corruption, such as candidate Nasri Asfura. “That would be the most disheartening scenario,” he admits. For him, a democratic backslide in Honduras would be like reliving all the fears and ghosts of Nicaragua.

| Cookie | Duración | Descripción |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |