January 3rd is the date on which academics and historians have marked as the resurgence of an old doctrine that is over 200 years old, and which, over the decades, has transformed the course of an entire region. For the first time in many years, the United States militarily attacked a Latin American country, making clear its vision for the hemisphere. With the capture of Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela, the Monroe Doctrine was revived, an old and controversial policy that brings the present closer to the dawn of the 19th century.

Just a decade ago, the then Secretary of State John Kerry declared that this twentieth-century worldview was dead. Today, under the second term of the Trump administration, it has returned in a revitalized form. To understand how the United States has returned to its role of sheriff, in the regional context, it is necessary to rewind two centuries to understand an idea that today seems central to the movement to Make America Great Again (MAGA): “America for the Americans”.

From shield to sword

In 1823, President James Monroe, advised by John Quincy Adams, drew an imaginary line across the Atlantic. Any European attempt at recolonization of the young American republics would be seen as a hostile act against the United States. In return, the nation would not interfere in European political affairs or wars and would recognize existing colonies in the Western Hemisphere.

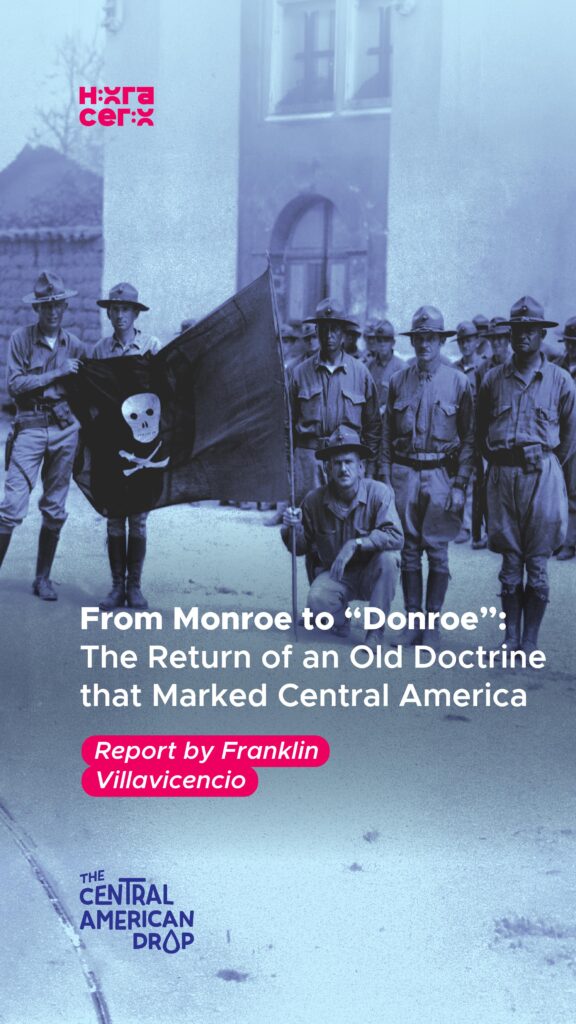

The premise of containment in the face of what were then considered imperial threats was short-lived. In 1904, President Theodore Roosevelt added an amendment, known as “Roosevelt Corollary”, in which the logic of the doctrine changed. If the United States was not going to allow Europe to intervene, collect debts, or impose «order» on the young and volatile republics, then a kind of international police force was necessary. And the United States would assume that role.

With this corollary, modern interventionism was born. Under this premise, the US Marines militarily occupied Haiti, Nicaragua, the Dominican Republic, and other nations during the mid-20th century. It became a tool of control and influence that would justify coups and allied governments throughout the region.

Maureen Meyer, vice president for programs at the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), who has decades of experience monitoring the region, emphasizes that the resurgence of the doctrine is not an isolated phenomenon. She recalls that, since its support for the military coup in Chile in 1973, the United States has maintained a stance of intervention, which included training death squads in Central America during the 1970s and 80s. For Meyer, after three decades of an approach based on institutional cooperation—such as the Plan Colombia at Mérida Initiative—, the hemisphere now faces a breakdown of that bilateral model.

The «Donroe» Doctrine

In September 2025, the Donald Trump administration published a National Security Strategy in which the Monroe Doctrine is revived. The motive is to restore the prominence of America (in this context, America means the United States) in the Western Hemisphere. The “Trump Corollary” has come into effect.

The security strategy also set priorities for Washington. “The other aspect I think is worth highlighting is the lack of attention, or even mention, of issues such as promoting democracy and human rights as central elements of U.S. foreign policy. Those disappear from the documents. There isn’t even a mention of human rights,” Meyer explains.

The new doctrine explicitly states that the United States will “deny non-hemispheric competitors” control of strategic assets in the region. In practice, this returns the world to the era of spheres of influence. That is to say, the Trump corollary has been established against the backdrop of China’s economic, political, and social growth in the region and security agreements with Russia. However, the analysis notes that, unlike other narratives of the past, this one prioritizes transactional value over ideology, and certainly not democratic considerations.

According to Meyer, if Trump’s first term was «transactional,» this second term has escalated toward «coercion based on threats.» The use of tariffs, individual sanctions, and even direct military force—as seen in Venezuela—marks an era where Washington no longer hesitates to use its power to impose its interests.

The region facing this new order

While in recent months the regional focus has been on countries with potentially more visible conflicts, such as Venezuela, Mexico, and Colombia, Central America has also been affected by this new context. According to Meyer’s analysis, the region has been configured as follows:

El Salvador: Nayib Bukele has positioned himself as one of the biggest beneficiaries of this new power dynamic. Amid his constitutional reforms and reelection bid, the country has served as a detention center (even for Venezuelan citizens) at the direct request of Washington. It is also an example of how, under Donald Trump’s transitional policies, human rights and democracy are not given due consideration.

Honduras: During the election process, Trump openly endorsed like-minded candidates under threat of withdrawing cooperation, which may have been a defining factor in the process.

Nicaragua: The Ortega-Murillo regime is keeping a low profile, trying not to “make a fuss” while facing potential reviews of CAFTA and new economic sanctions. It has released political prisoners, but maintains control and repression in the streets.

Costa Rica: The country seems to be leaning towards imported models, such as Bukele-style mass incarceration, reflecting an ideological alignment with the United States.

| Cookie | Duración | Descripción |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |