Sadie Rivas was left waiting for a special shipment that never arrived. It consisted of a book — she never learned the title or its author — a bag of ground coffee from the Nicaraguan mountains, another bag of rosquillas (a type of salty, crunchy biscuit very popular in Nicaragua), and a package of pinolillo (a sweet cornmeal and cacao based drink). On May 16, she spoke with her father. It was very early in the morning, she recalls.

Sadie had previously received other gifts from her father. It was a form of presence amid the absence that exile brings. Sadie, 25, has been in exile in Costa Rica for seven years due to the sociopolitical situation in Nicaragua following the April 2018 protests. When she left the country, she was 18 years old and part of that generation of young people who, fed up with repression, rebelled in their schools or universities and went out to protest. It was her father who encouraged her to go into exile. It was he who helped her cross.

Aníbal Rivas Reed — Sadie’s father — is a 61-year-old former Nicaraguan soldier. During his career, he rose to the rank of captain in the Sandinista Popular Army (EPS) in the 1980s. Aníbal enlisted when he was just 12 years old in the military service promoted by the FSLN in that decade. He had to take up arms in defense of the Sandinista revolution, unaware that, many decades later, the Sandinistas themselves would end up forcibly disappearing him for more than 40 days. Until 1990, he served as a captain in the EPS in northern Nicaragua, one of the harshest regions during the conflict. During that decade, following the peace accords and the professionalization of the Army, Aníbal gradually distanced himself from the military, embracing civilian life.

Despite being a retired soldier and an avowed dissident of the FSLN, Aníbal knows the party from the inside and knows what it’s capable of. That’s why, when the repression intensified in 2018, he himself took it upon himself to help his daughter, Sadie, leave the country to safety. «I remember that the only times I spoke to my dad—during the first days of exile—I would say, ‘Dad, please send for me. I’m going crazy, I have so many nightmares, I feel alone.’ I told him: I don’t have friends, I can’t go out, I don’t know anyone, I don’t have money, I don’t have anything. On a couple of occasions, he started crying and apologizing, telling me that, despite everything, and despite all the pain I felt, he would never allow me to return.»

Aníbal knew, possibly, what the party might be capable of when it felt socially and politically suffocated. And that the exile of his family, at his own expense, would be able to protect them. He’d had to go into exile himself. He had exiled himself during the final years of the Somoza dynastic dictatorship, when he was barely nine years old. His mother, Mirna Reed, was a guerrilla fighter in the 1970s who fought in the department of Matagalpa. The family’s exile also took place in Costa Rica, a country where exiles from two dictatorships in the last 60 years have sought refuge. Aníbal returned at twelve to enlist. And since then, he has never returned to exile. He stayed in Nicaragua.

Only one day passed after that call, in which Aníbal had promised Sadie to send her a book, coffee, some doughnuts, and a pinolillo. He was arrested on May 17, 2025, in Matagalpa, his hometown and where he lived. His arrest occurred as part of a raid against former military personnel and ex-officials of the Frente, including members of what was known as «historical militancy.» Among those detained that month were retired General Álvaro Baltodano, former soldier Denis Chavarría, and former Lieutenant Colonel Ronald Paul Leiva Silva, among others.

From then began 42 days without knowing his whereabouts. 42 days without his geographical location. 42 days of disappearance.

Until June 27, it was learned that Aníbal was sentenced to 50 years in prison for the crime of treason. His daughter reported that this sentence was carried out in the midst of an arbitrary trial, without conditions or the right to a fair defense. Similar to others that have occurred in Nicaragua over the past seven years. A spurious trial in a country without guarantees or rule of law.

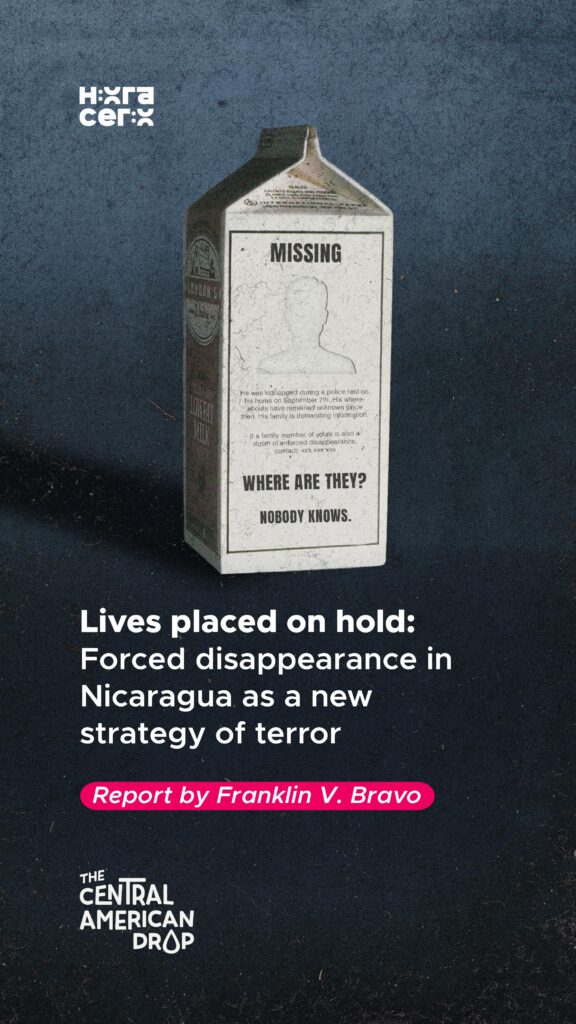

Disappeared. Common language usually uses it as a participle, in the present continuous. Suspended. The Royal Spanish Academy (RAE) emphasizes two central features: uncertainty of life, lack of information. The UN classifies it as: «Arrest, detention, deprivation of liberty (…) by agents of the State or with its acquiescence, followed by a refusal to acknowledge said deprivation or to reveal the whereabouts, leaving the person outside the protection of the law.» Dictators use euphemisms: «As long as a person is disappeared, they cannot receive special treatment, because they have no entity. They are neither dead nor alive… they are disappeared,» said Jorge Rafael Videla.

And yet, being disappeared is not just a concept. Since July 12, 2024, the question «Where is Fabiola?» resonates among her colleagues and friends. Because truly, no one knows where the journalist and cultural promoter Fabiola Tercero is. A year has passed and no evidence has emerged after the police raid on her home, located — a significant fact — within the security perimeter surrounding the house where Daniel Ortega and his family live in Managua. For the journalist — who had given away more than a thousand books through her project “El Rincón de Fabi” — the verb became destiny: she was trapped in that suspended time.

The Nicaraguan Mechanism for the Recognition of Political Prisoners explains what this suspension causes: it places the family “in constant stress and despair” and spreads “an atmosphere of terror in society.” Thus, each day without news prolongs the aggression: the crime continues to occur as long as Fabiola — and the other disappeared people — remain outside the protection of the law and the embrace of their loved ones.

The Mechanism works with methodologies to protect the silent work of those who collaborate on it and try to document the situation, but they also encounter challenges, silences, and difficulties in the documentation process. All of this has been caused by the brutal climate of repression, censorship, and the abolition of rights and freedoms that the Ortega-Murillo regime has imposed on Nicaraguan society since 2018. A recent report by the Mechanism details these human rights violations: 54 opposition members imprisoned and 15 people disappeared.

And this silence, this lack of information, is what surrounds Fabiola’s case. Where is Fabiola? No one knows, no one dares to approach her home. The regime has neither issued a sentence nor admitted to having her in custody. A cloak of impunity and fog prevails.

With Fabiola’s disappearance came the suspension of the operation of an independent, self-managed cultural project in Managua — significant words in a Nicaragua where culture, education, and spaces of any kind are controlled by the regime. The paranoia has spread so far that even equestrian and horse riding associations have been shut down by the dictatorship. All in an onslaught driven by the logic of control and the monopolization of any private, entrepreneurial, or independent initiative.

So «Fabi’s Corner» focused on sharing books, readings, and authors. On ensuring that literature circulated in a country where fiction seems to be the only escape to utopias and hopes. «I asked Fabi why she started this project, and she told me that, as a child, her only escape was books. That much of what she had achieved was due to the habit of reading, and that it was essential to encourage that,» says Alexa Zamora, a Nicaraguan activist exiled in Spain.

Alexa studied with Fabiola for several years in elementary school in Managua. «We were the stereotype of girls who weren’t part of the group and always walked alone. I think that defined us a lot as friends, along with two other friends we had.» Upon entering high school, Alexa dropped out of that school and lost track of that friendship until adulthood, when Fabiola was a journalism intern at a media outlet and Alexa was assessing an education plan.

“For the past seven years, I know what it’s like to work with victims. I’ve worked with political prisoners, I’ve documented cases of torture, and to think that someone so close to me is in a situation like that… Having a close friend who is a victim of forced disappearance by the State is frustrating and painful,” she adds.

The Central American Journalism Network classifies Fabiola Tercero’s situation as a forced disappearance because no authority in Nicaragua recognizes her detention. There is no known record of a sentencing or imprisonment. Friends of Fabiola, like Alexa, have also had no contact with her family or her close circle. All of this further complicates the journalist’s situation.

“In Fabiola Tercero’s case, the information has been very limited, and that puts her at increased risk. To date, we don’t have detailed information about what could have happened, not even with hypotheses,” explains Adolfo Lara, legal officer for Latin America for the organization Raza e Igualdad, which has documented the situation in Nicaragua.

For Lara, the case involves a series of risks that increase from an intersectional perspective: because she is a woman, because she is a journalist, even because she is a human rights defender. Documenting cases and creating hypotheses is increasingly a difficult task for organizations like Raza e Igualdad. This is largely due to the closure of civic space and the lack of testimonies and evidence.

Added to this is the exile of the families of the disappeared. “We are not in Nicaragua so we can go and demand answers every week, but we have also been insisting with the international community, and they have not received a response either,” Sadie said, describing the lack of information surrounding her father’s disappearance before his sentencing.

The Ortega and Murillo regime has been employing this strategy for a long time. Enforced disappearance has been a common practice for seven years. According to the Nicaraguan Mechanism for the Recognition of Political Prisoners, it is present to a greater or lesser extent in almost all detentions of political prisoners. Previously, the periods were usually days, a week, and then the detainees were presented in a theatrical trial. Since 2024, the difference lies in the fact that the practice has intensified and the periods are much longer.

“When these things happen, the person is at grave risk of torture and other cruel treatment.” There is an impact on all aspects of the lives of the families of the disappeared, because it can also lead to marginalization in the community,” the source explains.

Despite the closure of civic spaces, the cancellation of protests, and the state of terror imposed by the regime, support for families is essential. They are invisible networks of solidarity, in which safety advice is shared. There is even an underreporting of imprisoned or missing people, whose cases or names are not public, but are documented. Anonymity is a form of protection.

“We understand the terror, the fear, the self-censorship, but there are still ways to protect information and ensure that national and international oversight and monitoring agencies know that anonymous people exist and know what their cases are, but there is a humanitarian commitment that their identity will not be revealed,” he adds.

This silent resistance, in the shadows, can be essential for future trials. And for that, it is also important. The complaint. Through an encrypted email (mecanismopresospoliticos@proton.me), cases are received and reports of detentions, disappearances, and other human rights violations that the regime may commit are documented.

In Nicaragua, disappearance is still a developing phenomenon. Practices are beginning to be documented, case by case. However, a huge gap persists in how this absence is experienced and what resistance strategies are being implemented. Because resistance is precisely taking place in the midst of a dictatorship.

| Cookie | Duración | Descripción |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |