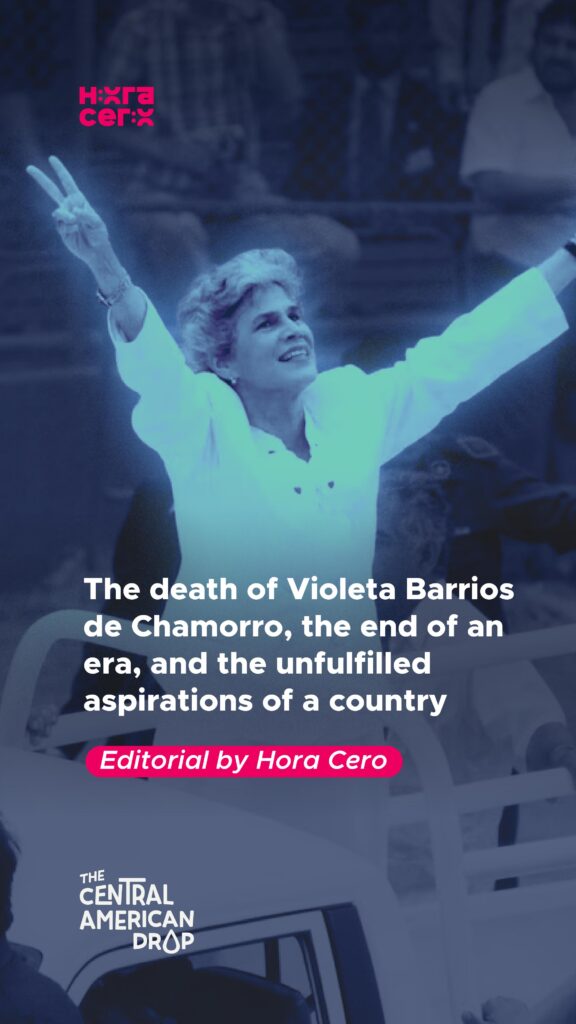

On Saturday, June 14, Violeta Barrios de Chamorro passed away. This former president was the most recognizable figure of the early 90s political transition out of Sandinismo in Nicaragua, whose coming to power ended a US-funded armed conflict. Rather than dwelling on her maternal role, which helped her to reconcile opposing sectors during one of the most tense moments in the nation’s history, we would like to reflect on how her death mirrors the end of an era. One where the dreams of peace, freedom, and democracy continue to highlight a debt that is owed to the Nicaraguan people.

To think about the end of the war – and subsequent disarmament and integration into civilian life of thousands of combatants – inevitably brings to mind photographs of Violeta Barrios and the commanders of the Contra at the ceremonial disposal of hundreds of rifles, an image that would be the basis of the symbolic “Beacon of Peace” memorial. This was the only post-war memorial that existed in the country, and was demolished by order of the current dictators of Nicaragua in their attempt to erase any vestige of a government before their own, especially if that government aroused any kind of sympathy among the people. Another legacy of the administration under Doña Violeta (as she liked to be called) were the Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs), a series of drastic economic measures, endorsed by international financial organizations, that were responsible for the mass layoffs of public workers, the sale of state-owned companies, and the reduction of social programs in an effort to improve the public finances of a country with one of the highest inflation rates in the world at the time.

Democracy brought with it the bitterness of unemployment and extreme poverty. Markers of human development declined sharply, and indicators of hunger and infant and maternal mortality increased. Guatemalan sociologist Edelberto Torres Rivas used the term “bad democracies” to describe the governments that were installed in Central America after the Peace Accords. He used this pejorative, which may sound a bit naive, to exemplify how this return to democracy dashed the hopes of countries that dreamed of substantial changes beyond electoral simulations and the separation of powers. These bad democracies devolved into inefficient, weak states, co-opted by corporate interests, and lacking credibility. Under this situation, the word «democracy» became nothing more than a meaningless label. It’s no coincidence, then, that 35 years later, we find ourselves with a region anchored to the authoritarian frameworks it seemed to have escaped.

The National Opposition Union (UNO) was formed in 1987 and was a motley coalition of 14 political parties whose objective was to unite around a common enemy: Sandinismo, and to do so beyond any ideological ambition or political consensus. This alliance began to crumble as soon as their first elected presidential candidate, Violeta, took power. Once the enemy was considered defeated, these different factions had many problems reaching a consensus, and some accused Violeta and her close circle (which included her campaign manager and son-in-law, Antonio Lacayo) of violating previous agreements. Today, over three decades later, a new generation that was born into democracy is, ironically, facing the same dilemma as UNO. It is confronting the same political party, still led by Daniel Ortega as the perennial candidate of the FSLN. The difference this time is that many of the political figures from that period are closer to death than to an influential political life.

The historian Antonio Montero reflects on how Nicaraguan politics has been mired for decades in the debate between Sandinismo and anti-Sandinismo. Like UNO, the Nicaraguan opposition seems bogged down in this discussion, making the end of Sandinismo its main banner and ideological project. The underlying question is how we expect that continuing the same pattern of antagonisms will not bring the same results as 30 years ago: being governed by a coalition with no aspirations other than the defeat of the enemy. Under this system, the well-being of the Nicaraguan people always ends up being left out of the equation.

| Cookie | Duración | Descripción |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |