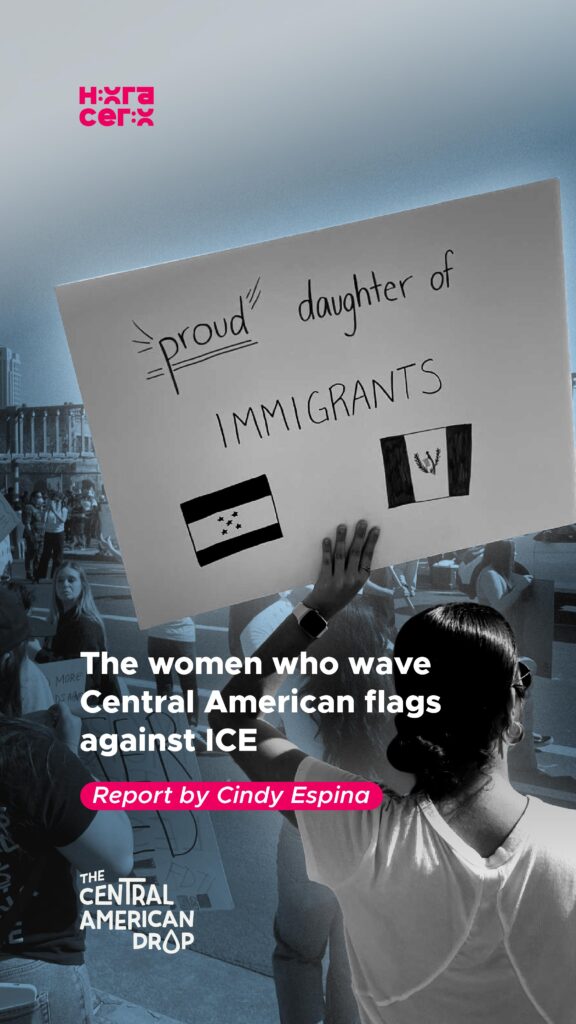

This is the story, told through virtual proximity, of two women with Central American roots who brought out the flags of Guatemala and El Salvador, showing up as blue dots in a sea of green, white, and red amongst dozens of Mexican flags. This is how the lives of these two protagonists, who have had slightly different paths, converged in the demonstrations in Los Angeles that have developed since June 6th. These demonstrations have spread from their prominent origin in LA to different cities in California and across the United States, protesting against the escalation of violent raids carried out by the Immigration and Customs Enforcement Service (ICE).

For an entire week, the streets of Los Angeles were filled with protesters peacefully demanding that ICE leave their city, amidst an unparalleled attack against migrants. For these protestors, taking to the streets and confronting officials complicit in violently implementing a deportation policy face-to-face is one act of resistance in a series that they have carried out as a community to keep immigrant families safe and united. It is a demand for their right to stay, to live here.

Many of these protests were met with police violence. Amidst rubber bullets and toxic clouds of pepper spray, thousands of people gathered to block major city thoroughfares, a tactic notably seen during the Rodney King riots. In 1992, when police officers who had been arrested for brutally beating an African American man named Rodney King were acquitted, the city of Los Angeles responded with protests, riots, and uprisings.

In the following week, on the other side of the country in Washington, DC, President Donald Trump was preparing to attend a military parade on June 14 – his 79th birthday – to celebrate the Army’s 250th anniversary. At the same time, with the rest of the country feeling animated by the resistance of Angelenos, a march had been planned to take place on Trump’s birthday to denounce his government’s policies that many consider authoritarian. That is why the movement is called: “In America we don’t have kings”.

Christina Roca, 26 years old and originally from Connecticut, on the east coast of the US, has attended the protests against ICE in California since they began. The June 14th march against the Trump administration was the last protest she attended. Her reasons for taking to the streets are rooted in the history of her parents and family: her father is Guatemalan, and her mother is Honduran. Both arrived to the US in the 1990s and obtained American citizenship in 2009. However, some of her uncles, aunts, and cousins in the country are still undocumented and at risk within the US immigration system, despite having lived there for a large part of their lives.

This situation, which has plagued her family circle for her whole life, has been the greatest influence on her work and beliefs. Because of this, she studied Sociology and Global Studies, which led her to connect with organizations supporting the migrant population on the border between Mexico and the United States. She moved to the West Coast, where she currently lives, to work in legal assistance for unaccompanied migrant children, but budget cuts by the Trump administration defunded the organization with which she worked, preventing her from continuing this work.

So for Christina, taking to the streets of California, primarily in the city of Santa Ana, was a natural continuation of the intersection that has run through her personal and family life into her work. A path that ran through her childhood and into her professional life. A path that she has also found in the protests against ICE – a space to continue organizing collectively on behalf of the immigrant community in the United States, and on behalf of her family.

From her desk chair, where she shifts from side to side as we talk from a distance, a smile crosses her computer screen to reach mine as she says with great enthusiasm that she is interested in joining the collectives of Rapid Response, focused on supporting people who are intended to be detained by ICE. She also mentions that because she currently has a part-time job, this summer she will go to support the protests that gather outside meetings of the government of California to pressure the state police to stop supporting ICE in its work of persecuting the Latino immigrant population. She also has planned to get a Honduran flag to wave during the protests. She says it frustrates her that she still can’t find one that links her to her mother’s origins, but for now she only has a small one from Guatemala, which she has waved throughout June in various Californian cities.

Jazmín Tobar, 37 years old, has a life and family story marked by social organizing and protesting in California. Born in Los Angeles, she is the daughter of a Salvadoran father and a Honduran/Salvadoran mother, both refugees from the war in El Salvador during the 1980s.

She tells her story over video call from her cell phone. Holding the phone with one hand, she uses her other hand to reinforce the words she speaks – words which flow very quickly, like a story she’s told several times before. Jazmín begins by talking about her parents, who taught her about social justice, but didn’t want her to be involved in political affairs or activism. But her parents’ wish did not come true, because in March 2006 she organized her classmates to attend “The Great March” to demand that a law which made being undocumented a crime not be passed.

“From then on, I didn’t stop,” says Jazmín, a laugh creeping in as she remembers that she did everything that contradicted what her father and mother wanted. Jazmín Tobar holds a doctorate in Social Work and is a professor at California State University, Department of Central American and Transborder Studies. She teaches about the recent revolutionary periods in Central America and the resulting diaspora in the United States. She proudly states that it is the only research department focused on Central America in the US.

After more than two decades of attending demonstrations, Jazmín now leads more of the logistics of these protests, especially to ensure the safety of her neighbors and colleagues. But all this time, she hasn’t just participated in the protests; she’s also a knowledgeable narrator and expert on the history of social movements in Los Angeles. She states that the June marches against ICE have united the city’s grassroots organizations and that this activation has led them to be more strategic.

Because it’s summer, the doctor of social work says she has more time to dedicate to activism, where her work focuses on supporting the Central American community in LA. One of her roles is with the collective Rapid Response, and she tells me that just yesterday, she had to go to the southern area of LA to answer a call asking for help in stopping and documenting ICE raids carried out there. Jazmín says that ICE didn’t achieve its objective that day; they left the area. She believes it was because so many people came to support the families who were being threatened. This gives her great satisfaction, although she restrains herself because she prefers not to let her guard down.

On other occasions, as part of her work, she has had to support entire families in making a plan in case they are deported. For her, this is the most difficult part of all her community work. This act of solidarity is also a mourning of the progress of policies and laws that encouraged her to take to the streets in March 2006 alongside hundreds of Angelenos, and for which she continues to fight on the streets of her hometown.

However, teacher Jazmín Tobar also finds small moments of resistance that bring joy, such as waving the flag of the country where her parents were born. At the protests in Los Angeles in early June, she went out to wave the Salvadoran flag – the flag that unites her parents, which she also considers her own. For Jazmín, with that little waving of the blue and white flag, she highlights the large Central American community in LA. She says there are more than a million Central Americans in LA, but the media narrative always highlights the population of Mexican origin.

“There are many people who say right now that because you are Salvadoran you cannot have pride, because Nayib Bukele is a dictator, and I understand that criticism and I understand the problem any country has with nationalism, but (waving the flag of El Salvador) is also a way to show where we come from and we cannot let that story go unspoken”, says the activist, professor, and academic from Los Angeles during the interview. By the rhythm of her words and the back and forth of questions that she asks herself, it seems to be more of an internal reflection than an answer.

Christina Roca also believes that waving the Guatemalan flag at protests against ICE is an act of raising awareness for the Central American community. Laughing, she says it’s overwhelming to see the amount of enormous Mexican flags while she carries her own small blue and white flag, but from time to time, she has encountered several people at the marches who shout «¡hey chapina!” to greet her because they are also from Guatemala.

“I know that I have the privilege of being born here and of being able to go see my family, but at the same time I am proud of my roots and that is why I am going to have those flags in mind and at the protests, so that the effort that my mother and father made to come to this country, to give us the education and work opportunity, is not forgotten,” says Christina, with a slight clearing of the throat.

Although demonstrations in California cities subsided after the imposition of a curfew in LA on June 11 (8 pm to 6 am), community actions remain active, primarily in the groups of Rapid Response, where Jazmín has been part of a long-standing struggle, and where Christina seeks to build on it. Rapid response groups are currently a refuge that shelters immigrants and interrupts detentions with the aid of the community. They denounce the violent act of capture for deportation carried out by ICE in the United States.

| Cookie | Duración | Descripción |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |