In El Salvador, María* works the land in her native department of Ahuachapán, bordering Guatemala. Every day she cares for and grows dozens of vegetables and aromatic herbs with which she feeds her four sons and daughters and her life partner, she also sells these products to the people of her farmhouse located in San Francisco Menéndez. However, María works on land that does not belong to her.

She tells HoraCero that the “solar” – as she calls the land where she farms – belongs to a man who migrated to the United States and is the one who rents it to her and another neighbor to grow their products. But, with the direct affront by Donald Trump’s government against migrants, the owner of the land has decided to return to El Salvador and build a house before being deported. María and her neighbor have 15 days to vacate the place.

«Now we have nowhere to put our garden. There we grow tomatoes, lettuce, green beans, cucumbers, aromatic and medicinal plants, everything. We grow these for our consumption and to sell in the community, so we buy the things we need at home. We are asking another woman if she will rent us land, if it doesn’t work out, we’ll see how we do,» she said.

Her partner suffers from diabetes and kidney failure. Given the lack of resources, she has decided to send only her 6-year-old son to study, who spends about 4 dollars daily to travel to school, while her daughters, ages 14 and 18, help her take care of the garden and sell her products. She states that, at least in her community, she does not know of any women who own the land they work on.

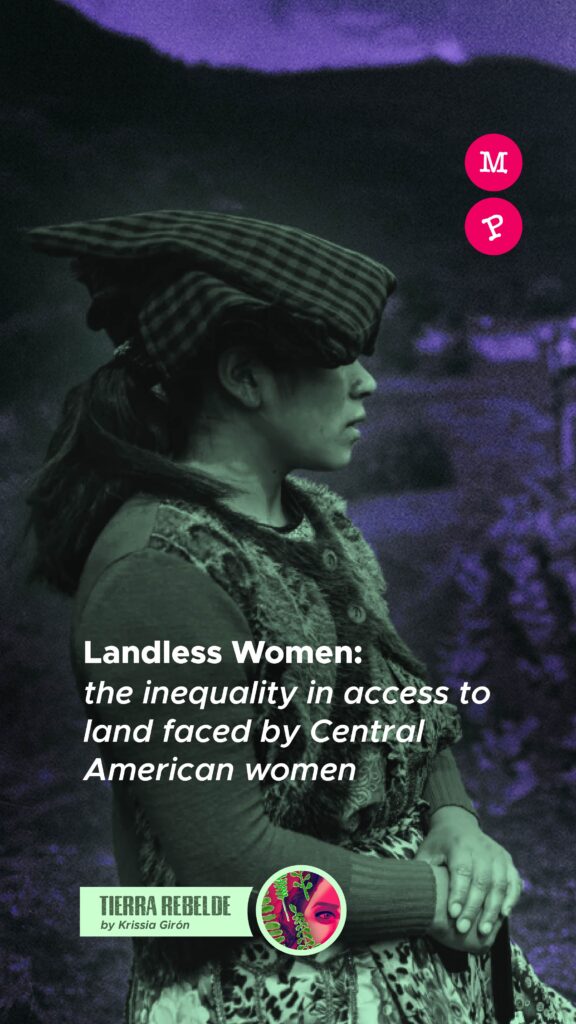

In Central America, women face great challenges in accessing land and having their own homes and land to grow food. According to the report “They Feed the World”, published by LatFem and We Effect, gender inequality in land ownership and ownership limits the economic and social autonomy of women.

In the case of El Salvador, 37% of those surveyed by the study stated that they do not have a property title or do not know the owner of the land they work on. Many of the lands granted to women come from cooperatives created after the agrarian reform of 1980. However, men continue to predominate in property ownership.

The 2023 Household and Multipurpose Survey indicates that, until that year, only 15,590 women owned the land they worked. Women are responsible for caring for life in their communities, but without access to land, their ability to support themselves and their families is limited.

“Women have been excluded, we have been denied the property right, the patriarchal system and the capitalist system labels us as someone else’s property,” explains Carolina Amaya, from the Salvadoran Ecological Unit (UNES).

The LatFem report also highlights that peasant women must deal with the lack of resources to improve the land they rent or inherit. In many cases, they are given land in dangerous areas or without access to basic services, which forces them to migrate and leaves them in an even more vulnerable situation.

They are also given very small portions of land, unlike men. For example in Nicaragua, a study of the Women, Land, and Rights Initiative, states that 59.2% of rural women in this country have access to land smaller than two blocks. This same report indicates that 40% of rural women access land through purchase or inheritance.

In this regard, the report of the Nicaraguan regime, presented within the framework of the anniversary of the Beijing agreements on women’s rights, in 2024, claims to have benefited 370,753 women with property titles.

In the case of Guatemala, the LatFem study details that in 2008, according to the National Agricultural Survey, women represented 18.2% of those who produce food in that country and, according to a study by the Presidential Secretariat for Women (2013), it was more common for Guatemalan women to have access to land through usufruct and colony, revealing their little power to fully decide on the land they work.

Estaba en Bélgica, editando las primeras imágenes. Y recordando lo que habían dicho los campesinos: «Solo nosotros protestamos, pero toda la gente tendría que salir de sus casas para decir ¡No!». Y entonces veía cientos de miles de ciudadanos en las calles, los diferentes movimientos sociales uniéndose, los campesinos, el movimiento estudiantil, los ecologistas, las feministas, la comunidad LGBTQ+. Y la represión estaba siendo super violenta. Después de la Marcha de las Madres, donde tantos jóvenes cayeron muertos, matados por las fuerzas del gobierno, decidí regresar a Nicaragua para seguir acompañando la evolución de esta lucha pacífica, como podía, sin saber lo que iba a pasar.

El país estaba completamente bloqueado por barricadas. Volví a encontrarme con Doña Chica, encontré a los estudiantes que estaban ocupando la UNAN y pude pasar tiempo con ellos, para entender qué les había empujado a entrar en oposición de forma tan valiente contra un gobierno armado, y cómo estaban viviendo esta situación. Conocí a las madres que dormían en el suelo frente a las puertas de la cárcel de El Chipote, intentando tener noticias de sus maridos, de sus hijos, que estaban encarcelados allí, y siendo torturados, por haber protestado, por haber hecho una barricada, por haber atendido a un herido.

Cuando el gobierno por la fuerza aplastó a los opositores en julio de 2018, ante la violencia de la represión, muchos se vieron obligados a exiliarse. Los encontré en el exilio en Costa Rica, donde se estaban curando las heridas y estaban reorganizando la lucha.

| Cookie | Duración | Descripción |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |