The Military Uniform of the Minister of Education

Maldito País

octubre 1, 2025

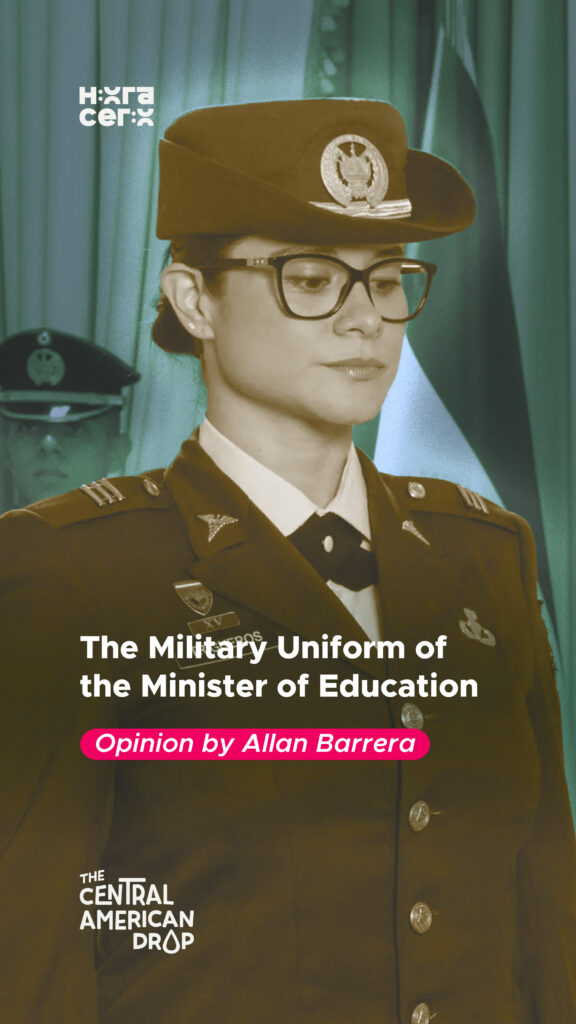

On August 14, 2025, El Salvador’s President Nayib Bukele appointed Captain Karla Trigueros of the Armed Forces as the new Minister of Education. She enters his office and sits at her desk in her uniform and soldier’s boots, as if she were a soldier returning from war. We are not criticizing her based on whether she is a woman or a doctor, as government analysts have tried to suggest, but because it is milica which evokes the dark military dictatorships that El Salvador suffered in the decades of 1930-1980.

Almost a day after her appointment, she issued a memorandum through the social media platform X. with disciplinary rules for public schools and institutes: clean and tidy uniform, appropriate haircut, proper personal presentation, and entry to school with a respectful greeting and order. Nothing new, except the media performance that amplifies the military ethos of order, discipline, and hierarchy that Bukele so desperately wants to promote and that confirms that the country continues to march down the path of prudishness.

Historians can tell us how many of the ministers during the military governments, from Maximiliano Martínez to Napoleón Duarte, were soldiers and whether they entered their Ministries in uniform, as did the current minister. Curiously, it was under the military dictatorship during the time of Fidel Sánchez Hernández (1967-1972), when an unprecedented youthful, rebellious and emancipatory creative energy was deployed from public education: in a moment of counterinsurgency openness, the playwright Walter Béneke was appointed to head the Ministry of Education and will boost an educational reform, which created the Bachelor’s Degrees in Arts and Diversified Studies and the National Arts Center.

The result, as Roque Baldovinos has shown in his book The Rebellion of the Senses (2020), was unexpected: far from channeling youthful rebellion into a policy of containment, the generation formed under that reform challenged the military ethos of discipline, order, and hierarchy. Some became radicalized and joined the guerrillas, changing the course of the country, which, fortunately, also exemplifies that the dominant power cannot guarantee its constant reproduction. There are always points of escape, rebellions that refuse to be absorbed by it.

I grew up in the 1990s, when everything that the reform had created was being extinguished with the precariousness of public education due to the neoliberal restructuring carried out by the governments of the Nationalist Republic Alliance (ARENA). This led to the closure of the arts bachelor’s programs and the impoverishment of the quality of public education. I suffered from this empty discipline in public school and at the institute where I studied high school, where the principals and teachers checked us upon entering, making sure that we had our shirts tucked in, that our hair was neatly trimmed, that our ears were free of earrings, and that the women’s skirts were below the knees. A tattoo deserved expulsion, as did a baby bump. That’s how I remember a classmate in eighth grade who was asked by her teacher not to show up the next day, at the Jorge Lardé Mixed Urban School in the San Jacinto neighborhood, to prevent her from setting a bad example.

This school discipline didn’t prevent some of my classmates from becoming gang members, nor did it prevent other students in the early 2000s from ending up the same way. If I survived, it was only because I liked metal and was more attracted to the rock aesthetic and culture of those years than the gang culture.

This failed discipline was repeated as if by inertia year after year, while poverty and inequality continued to make gangs, along with migration to the United States, an attractive alternative for youth, which guaranteed them a stake in the Salvadoran economy. Unfortunately, this custom remained intact during the FMLN governments, even though they added free uniforms, shoes, and glasses of milk and waived the tuition fees required by schools. And it extended to Bukele, who now praises it as an innovation.

If there’s an archetypal 20th-century uniform that symbolically encapsulates the former Salvadoran oligarchic order, it’s the military uniform. As late as the 1990s, as a residual culture, the middle class enrolled their children in military school in the hope of achieving a degree of social mobility and, with it, a small share of the landowning oligarchy’s feast, a status alongside the oppressors.

The Peace Accords and the shift to the new neoliberal order, which incorporated Central America into financial globalization, gave the illusion that the specter of militarism had been left behind; it seemed that the new financial and transnational elites no longer needed the Armed Forces as much. But the young businessman Bukele showed us that this is not the case; they continue to be a useful tool for subjugating working-class populations.

The military ethos isn’t biological; it’s not in our blood; it’s a cultural and historical construct that cuts across dimensions of power and class. Since the dictatorship (1931-1944) of General Maximiliano Hernández Martínez, and even before, it has continued to wield violence against the working class. A different logic and pedagogical processes operate in private schools, reflecting the class inequality between those who can afford private and public education. Bukele and his brothers weren’t subjected to this prison-like discipline at the Escuela Panamericana, the «fresco» school where they attended. Of course not: it’s the young people from impoverished neighborhoods and settlements who are subjected and oppressed by these rules, which are then reproduced by the business community through their human resources departments because, except for call centers, all other jobs require the same: trimmed hair, no tattoos, «proper personal appearance,» etc.

One looks at Bukele’s officials, like Communications Secretary Ernesto Sanabria, for example, who has never hidden his tattoos. He recently appeared with long hair and a shirt with a marijuana leaf on the chest, standing next to the legendary soccer star Mágico González. Hopefully, his government will one day legalize the use of the herb he wears so proudly, along with abortion and same-sex marriage. In the meantime, it only illustrates the governmental hypocrisy of its officials, who impose standards of conduct on the subaltern sectors to which they themselves would never be willing to submit.

Meanwhile, the Minister of Education is being exploited by the Presidential Palace’s propaganda machine in her soldier’s uniform, carrying a heavy historical burden. Her camouflage uniform and military boots represent the worst of 20th-century El Salvador; their fabric coagulates the 1932 massacre, the 60,000 deaths attributed by the Truth Commission to the Salvadoran army in the civil war (1980-1992), the disappeared and tortured, the Sumpul and Mozote massacres, and the new deaths and torture in Bukele’s prisons under his endless regime of exception.