Pablo Sibar is 69 years old. His voice echoes his experience, his work, and his dedication to defending the land. Although tired at times, he finds energy when talking about Térraba, the land that he and his Brörán people, alongside other Indigenous communities, have sworn to defend. He bears deep wounds from his struggle: threats to his life, arrests, assaults, and the recent loss of two of his companions, Jehry Rivera and Sergio Rojas. However, his conviction is clear: «Indigenous lands belong to Indigenous people.»

On August 10, he faced a new threat. Non-indigenous people invaded his farm, a 10-hectare farm dedicated to environmental conservation and community water management, which he has legally owned for 13 years. The police refused to evict them because they had a certificate issued by the Térraba Integral Development Association (ADI).

“It was a family that was working on my plot. They gave me a document that the ADI had given them. We had an altercation, the police arrived, we managed to get them out, but then the threats started, and they started saying I’m a land invader. I’ve filed two complaints with the Agrarian Court and the Criminal Court.»

Social, environmental, and human rights organizations, as well as representatives of indigenous peoples, consider this invasion to be «a pattern of dispossession, harassment, and violence» against indigenous territories, which threatens Pablo Sibar’s life.

To this day, the murders of Jehry Rivera and Sergio Rojas remain unpunished, according to Elides Rivera, a long-standing leader of the Brörán people of Térraba and Jhery’s aunt. She and her family are one of the strongest and most historic pillars of the defense of the territory.

To understand the danger of being Indigenous in the «most democratic and green» country in Central America, one must unravel the story of Pablo, Elides, Jehry, and Sergio, of the struggle of indigenous peoples to reclaim their territories, and of the strategies of those seeking to lay their hands on them. A conflict that has dragged as a 500 years old night, but which has taken various turns in recent history.

In 1978, Costa Rica approved the Indigenous Law, which determines in article 3 that indigenous reserves are “inalienable and imprescriptible, non-transferable and exclusive to the indigenous communities that inhabit them.» In addition, it indicates that non-indigenous people «May not rent, lease, purchase or in any other way acquire land or properties within these reserves,» since the transfer and negotiation processes are reserved solely for indigenous people.

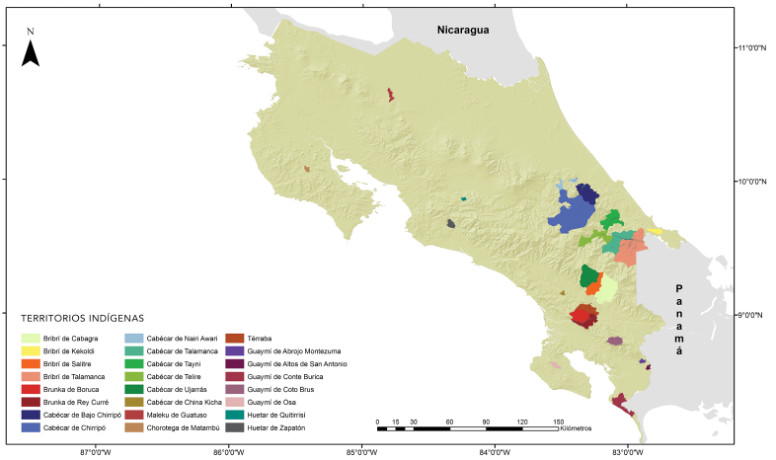

According to the 2011 Population Census, 104,103 people identify as indigenous, constituting 2.4% of the total population. These people are found in the 24 indigenous territories, distributed among eight indigenous communities: Bribri, Cabécares, Térrabas, Bruncas, Ngöbes, Malécu, Chorotegas, and Huetares.

An Executive Decree of 1982 created the Integral Development Associations (ADIs), which legally represent indigenous communities and act as their local government. Each indigenous reserve has an ADI that, according to the decree, processes «any action or project of public or private organizations or individuals.»

Over time, Indigenous peoples viewed the ADIs’ actions as «a betrayal,» as certificates and documents were issued that handed over Indigenous territories to non-Indigenous people, such as farmers, ranchers, landowners, businesses, among others.

«It turns out that this Development Association colludes with all the landowners and begins to certify them and grant them rights, ignoring the Indigenous Law. I have faith that this process we are pursuing in court will demonstrate that these ADIs are causing enormous problems for the population, because instead of defending the lands, they are handing them over,» Sibar explained.

Faced with the obvious non-compliance with the Indigenous Law, the State has turned a blind eye. Jeffrey López, Director of the Association of Popular Initiatives Dïtso, says there is clear inaction in the face of the delivery of these documents that dispossess the indigenous population of their lands.

“Land recovery is a State imperative. The State has the obligation to recover the lands and return them to Indigenous peoples within the framework of these executive decrees creating the territories. There is a debt because the State is not doing enough to return the lands.”

Then the communities organized themselves. Sibar is a member of the National Front of Indigenous Peoples (FRENAPI) and the Council of Elders of the Brörán people, organizations created by the population to defend their rights. He also works as a land reclamation worker, along with other men and women from the territories. Lands that have been «taken» by non-Indigenous people.

“Arguments will be heard claiming that the indigenous people are actually illegally recovering these lands. On the contrary, this is legal because they fall within the rights of indigenous peoples. This has generated a very strong reaction from groups, especially landowners and other groups linked to the criminal networks that have operated in the occupied indigenous territories,» López mentions.

This reaction has been violent. There have been threats and attacks against the indigenous population. In these contexts, we can evidence crimes against indigenous Sergio Rojas and Jehry Rivera. Pablo speaks with restrained pain about his colleagues. Sergio, a long-time defender and founder of FRENAPI, was shot 15 times in his home in Salitre, in the south of the country, on March 18, 2019. Three suspects were arrested and later acquitted by the Buenos Aires Criminal Court in Puntarenas in 2020.

For Pablo, the investigations into Sergio’s case «were not conducted as they should have been.» They maintain that it was commissioned and that the masterminds have yet to be found.

Jehry Rivera, for his part, was murdered during a land reclamation operation on a farm between Térraba Centro and the area known as Mano de Tigre on February 24, 2020. Rivera was provoked by several illegal landowners. There, he was beaten and shot twice, resulting in his death.

In 2022, at a central government event in Buenos Aires, Juan Eduardo Varela confessed to being the perpetrator of Rivera’s death. The entire event was captured on video and broadcast live. “I was the one who killed him.”, he said.

Varela was arrested and sentenced to 22 years in prison for the crime. However, in September 2024, the Cartago Criminal Court of Appeals acquitted him of the crime, arguing that the presented evidence did not allow the arguments of the Prosecutor’s Office or the plaintiff to be verified. The Court upheld the acquittal in January of this year.

Elides Rivera became involved in the struggle from a very young age, learning from Pablo and other historic leaders. Although her voice trembles when she recalls the murder of her nephew Jehry, she shows strength when she thinks of the courage of her sister and the women who faced that terrible blow at that time. “Of course, it’s an event that leaves you overwhelmed, devastated. But what sustained me was the strength of my sister, Jehry’s mother, one of Costa Rica’s most historic leaders.”

“I remember her that day. When we all arrived, she was standing there, surely waiting for us. She was standing in front of the path that led to a field. She told us: ‘I don’t want you to cry, I want you to be brave. We knew this could happen to anyone. It happened to Jehry, and what I need is for everyone to be there for me,” she recounted.

She and her family have filed appeals with the Court to overturn Varela’s acquittal and bring justice for the leader’s murder. She states that they seek to exhaust all legal remedies to ensure due process continues. However, she clarifies, «I do know that justice is something else and that it doesn’t reside in a court of powerful white men.»

Elides’s story is the story of the women of the Brörán people who, in the midst of their struggle for land, also recognized the inequalities they faced: dispossession, gender-based violence within and outside the community, the burden of being single mothers in a hostile environment, and the differentiated impact of the violence and discrimination they already experienced as Indigenous people.

«The worst enemy is fear,» she asserts with conviction. That’s why they have decided to confront it by organizing, learning about their rights, and speaking out to defend not only their territory but also the dignity of Indigenous women. Thus, they created a women’s organization that has been working for 30 years.

“Tiger’s Hand is a petroglyph, a rock with a jaguar’s footprint. The stone is large and is in the territory. It’s where our jaguar grandfather left his last footprints. So we said, ‘Well, here the best spirit that can accompany us, that can represent us, that can guide us is the jaguar. And we’re going to call ourselves: Tiger’s Hand Women.’”

Elides, along with Mano de Tigre, has promoted a comprehensive policy of resistance: reclaiming identity, protecting natural resources, and transforming power relations, starting from the home all the way up to institutions.

Costa Rica ratified the ILO Convention 169 on April 2, 1993. This commitment is to respect the rights of indigenous peoples, including the right to land, culture, and free, prior, and informed consultation.

The Central American country has been internationally recognized as a «green country» and is praised and held up as an example for its sustainable actions, protecting biodiversity and nature.

However, the stories of Pablo, Jeffrey, and Elides show that, today, this discourse contrasts with an uncertain future in environmental matters and with «shameful» contradictions, such as the lack of recognition of the Escazú Agreement, a treaty that recognizes the work of land defenders and commits states to their protection.

“The image has more to do with tourism and the marketing that past governments were able to establish. But the environmental situation in Costa Rica is at serious risk. There is a clear systematic weakening of environmental commitment, underfunding of the National System of Conservation Areas, and blatant corruption between the government and businesspeople who do business with the environment,” Jeffrey says.

Pablo Sibar adds that while his country «mocks itself by saying it’s a green country,» it doesn’t mention that the green areas are in indigenous territories, «and that these are territories that are being besieged by many companies, by many who want to enter and explore or exploit the resources we have in these lands,» Pablo reiterates.

For her part, Elides believes that despite the «beautiful» image of a democratic and green Costa Rica, its leaders «have lost their way» on this issue. However, she is convinced of her people’s resilience and their ability to change the system of dispossession under which they live. «My strength lies in resilience; it’s the grandmothers, grandfathers, and women of my people today.»

| Cookie | Duración | Descripción |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |