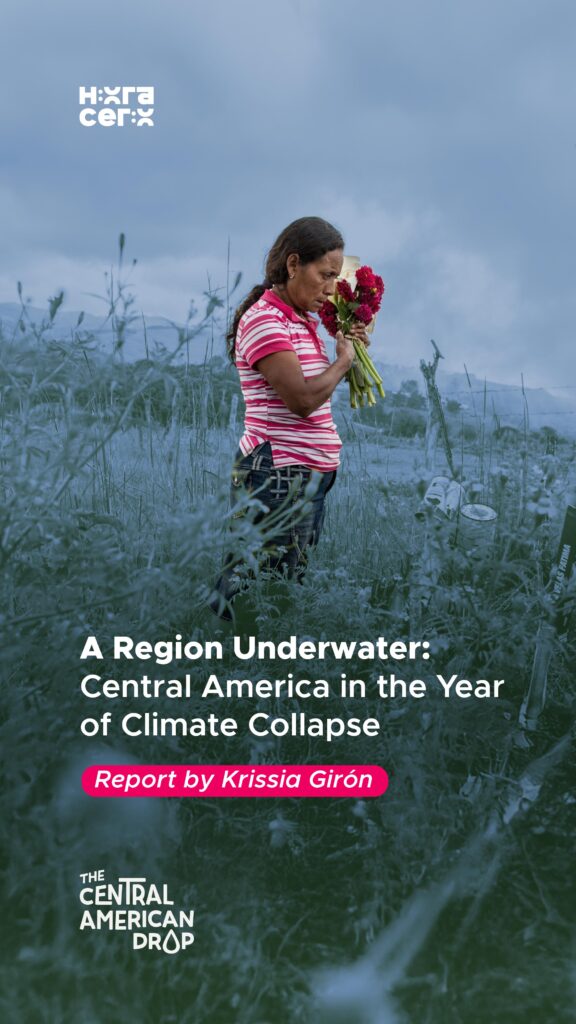

Since the beginning of the 21st century, data from different organisms have identified Central America as one of the regions most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. This forecast has been reinforced over the last 10 years, and 2025 has made it clear that, if this trend is not reversed, the region could see its already deteriorated environmental situation worsen, threatening all forms of life.

This year, Central America experienced an intensification of its climate vulnerability, considered the second highest on the planet. The first months of the year saw over 28,000 hectares of forest impacted in Honduras due to wildfires, and over 16,000 hectares in Guatemala for the same reason. In Guatemala, over 24,000 people were affected during the rainy season, and 45 died; while in Honduras, 35,000 people were affected, and hundreds were evacuated in El Salvador and Nicaragua.

The State of the Region report, produced by the State of the Nation Program in Costa Rica, indicates that the region’s situation is complex, environmentally unsustainable, and socially exclusionary. Five countries are experiencing an environmental deficit, four of them exceeding 43%. Alberto Mora, the research coordinator, explains that this deficit reveals the high consumption of natural resources and pollution generated at an accelerated rate in the region, preventing ecosystems from recovering.

According to Mora, the factors contributing to this environmental deficit lie in the consumption of fossil fuels, outdated transportation systems, rapid urbanization, and other environmentally unsound patterns of production and consumption. Furthermore, the climate crisis is intertwined with institutional crises and democratic backsliding in each country, making the poorest communities the most vulnerable to its severe impacts.

“The climate change scenarios for the region are truly alarming. Since it is a global phenomenon and our ability to modify its behavior is practically nil, we must find ways to lessen its impact on us. This is done by adapting our production systems and the way we carry out our social, economic, and human activities to reduce, as much as possible, the impact of this phenomenon,” he explained.

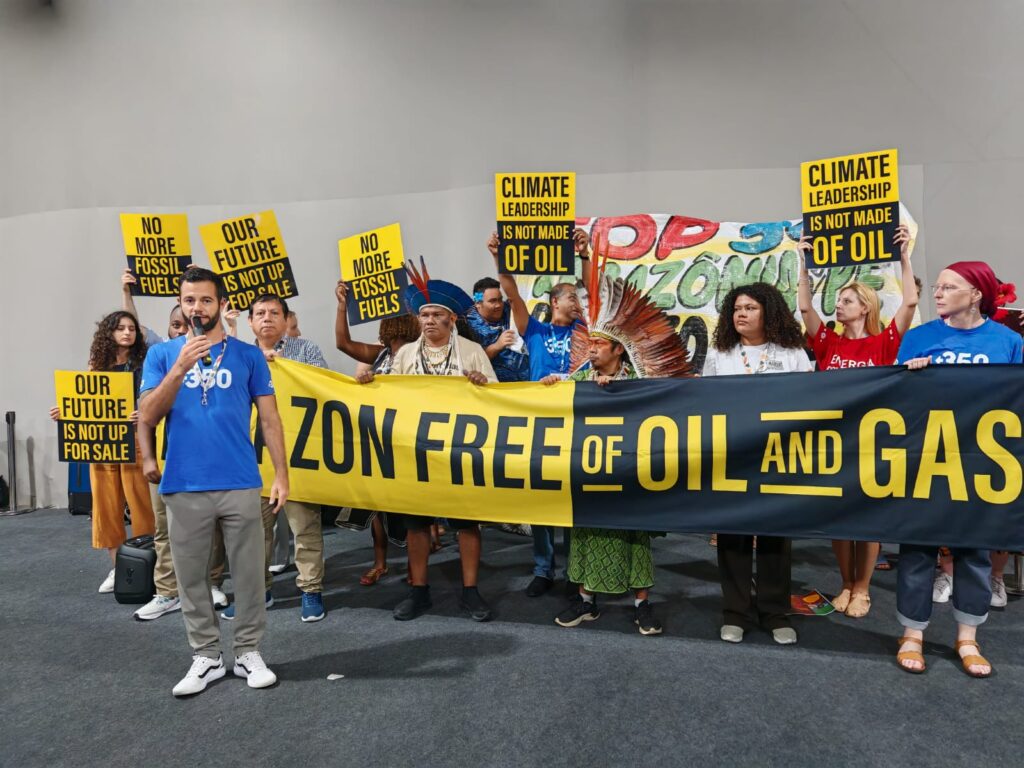

Demands for concrete actions to adapt to climate change and for more ambitious commitments from states were presented at COP30, held in Brazil. Environmentalists and organizations from Central America. They joined the global outcry demanding greater investment in adaptation actions, eliminating the use of fossil fuels, a just energy transition, and fair participation from all sectors.

This edition of the Convention took place within the framework of the 10th anniversary of the Paris Agreement, a treaty that commits countries to keeping the planet’s temperature rise below 2°C, through actions such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions and decreasing the use of fossil fuels. However, during the negotiations, there was a greater presence of representatives from the fossil fuel industry than at other Conferences of the Parties, with more than 1,600 people participating. 1 in 25 COP30 participants was a fossil fuel lobbyist.

COP30 ended on November 22 with several agreements and one of the biggest disappointments for environmentalists: in none of the final texts was the long-awaited roadmap for phasing out fossil fuels included. The Convention presidency stated that it would be created as a separate initiative, but outside the COP implementation process, raising questions about its practical implications.

Among other agreements, funding for climate change adaptation was tripled—from $40 billion to $120 billion by 2035—and a mechanism for a just energy transition was created. In this regard, Alberto Mora believes that Central American countries must prioritize the environmental and development agenda across various sectors and develop coordinated actions in international forums to truly receive the financial support they need to implement adaptation measures.

“The magnitude of the investments that countries like ours need to make, not only in infrastructure, but also in technology, in modifying production systems and supporting the entire population involved in this transformation process, absolutely exceeds the financial capacities of small and weak states like ours, also because of the magnitude of the impact and the investments required.”

2025 marked the passage of important legal processes for individuals defending the territory criminalized for their work, as well as indigenous peoples of the region seeking justice and truth for their communities, and sentences that aim to recognize events inscribed in the memory of each country.

From January to May, the trial was held against five former members of the Civil Self-Defense Patrol (PAC) for sexual violence, illegal detention, and torture against women of the Achí community in Guatemala. They were ultimately sentenced to 40 years in prison after the presentation of numerous testimonies from women who were victims of these crimes.

This historical process made it clear that the Guatemalan Army used sexual violence as a weapon of war against Indigenous women. The strategy was based on accusing the women of being part of the guerrilla movement to capture them and hold them captive, subjecting them to numerous human rights violations, torture, and ill-treatment.

Among the various cases of criminalized Indigenous leaders in Guatemala are those of Luis Pacheco and Héctor Chaclán, leaders of the Board of Directors of the 48 Cantons of Totonicapán, accused of illicit association and of being the public faces of the 2023 nationwide protests demanding respect for the general election results. This situation was repeated in January 2024, when the protests served as a pressure tactic to ensure the transfer of power from President Bernardo Arévalo.

Both were arrested in April 2025. Family members and lawyers have denounced the alleged manipulation of the judicial system, seven months after their capture. They claim that, despite the investigations concluding in June, the process has been deliberately stalled. In the same case, Esteban Toc, former deputy mayor of the Indigenous Municipality of Sololá, was also arrested on August 28th and is currently under house arrest due to health problems.

El Salvador awoke in 2025 with the new Mining Law, approved in December 2024, which allows the extractive industry to encroach upon territories of mining interest. This was one of the countries that saw an accelerated increase in the number of human rights violations, criminalized environmental leaders, and detained human rights defenders, resulting in a significant exodus of journalists and activists and the closure of social organizations that carried out vital work in these territories.

One of the processes that culminated in a favorable resolution was the case of the 5 leaders from Santa Marta, who began the year dragging a judicial process that began with their arrest on January 11, 2023, and that finally culminated in September 2025, with the sentence of the San Vicente Court that declared them innocent and free.

This would be the second declaration of innocence for the five from Santa Marta, since in November 2024, another court ruled that the criminal action was extinguished due to the statute of limitations, as it could not be proven that the accused had participated in the crime. However, the Prosecutor’s Office insisted on overturning this decision, and the trial was repeated in 2025 before a new court.

The new court also clarified that guerrilla organizations from the 1980s cannot be criminalized as illicit associations, an important precedent in El Salvador, where several former FMLN combatants are accused or detained in various legal proceedings. The Committee of Relatives of Political Prisoners and Persecuted Persons of El Salvador (COFAPPES) has registered 90 cases of political prisoners and those persecuted in the last five years. In 2025 alone, 28 incidents were reported.

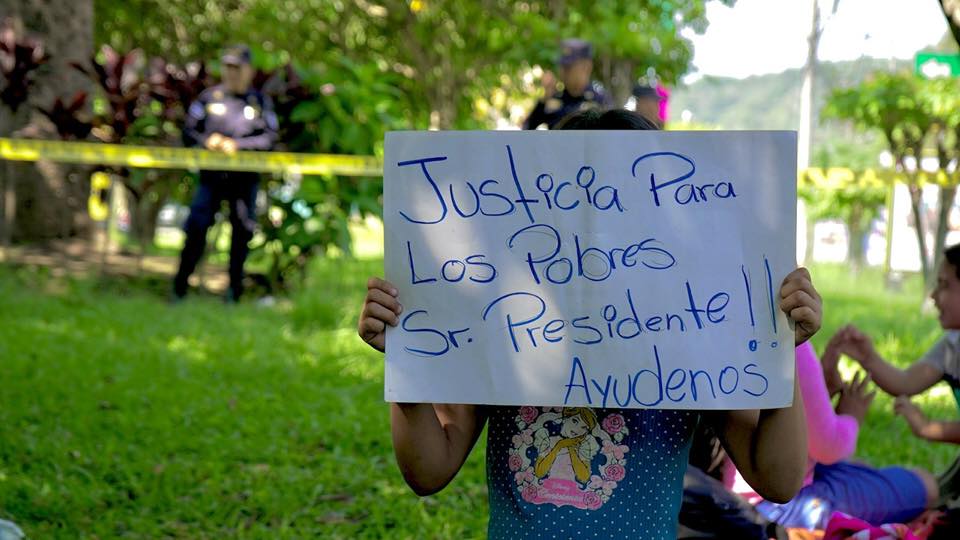

In the first months of the year, the communities that inhabit the El Bosque cooperative denounced that a court ruling would leave more than 300 families living in the area, located in Zaragoza, La Libertad, homeless. In May, after months of petitioning the central government and the justice system for answers, the families of the cooperative decided to hold a peaceful protest near the Presidential Residence, where the president and his family live and where a $1.4 million infrastructure project is under construction.

The government’s response: the deployment of over 100 officers from the National Civil Police and the Military Police, a unit not seen since the 1992 Peace Accords. Pushing, shouting, and crying began to dominate the live broadcasts of community media outlets. The police attempted to forcibly arrest several of the cooperative’s leaders. As a result, the cooperative’s president, José Ángel Pérez, was arrested on the spot, and one of the lawyers and human rights defenders, Alejandro Henríquez, arrested the following day, faced legal proceedings in the following months for aggressive resistance to arrest and public disorder.

Both were released on December 17th after requesting an expedited trial in which they had to plead guilty to crimes they did not commit. They were sentenced to two years in prison for resisting arrest and one year for public disorder. Through a suspended sentence, the prison term was replaced with three years of probation.

One of the most restrictive measures is that they cannot participate in activities for which they have been convicted. However, this rule does not apply to the practice of human rights advocacy, as their lawyers have explained.

The events leading to the repression against the El Bosque Cooperative created a point of no return in the country. The community journalists who covered the events remain in exile due to threats to their safety. This case was used by Bukele to justify the approval of the Foreign Agents Law (LAEX), which seeks to control and punish the finances of civil society organizations that “engage in political activities,” as he stated.

The Annual Report on Socio-Territorial Conflict in Honduras 2024 report published this year by the Center for Studies for Democracy (CESPAD), through its Observatory of Socio-Territorial Conflict, identified 58 socio-environmental conflicts in the territory. According to this analysis, the environmental progress made by this government is partial, fragile, and faces “serious risks of stagnation or reversal, especially in a context where decisions tend to prioritize immediate symbolic results over sustainable structural transformations.”

September 14, 2025, marked the first anniversary of the assassination of Juan López, a defender of the territory and community leader whose voice rose up against extractive projects in the Bajo Aguán region of Tocoa, Honduras. Almost a year later, neither the Public Prosecutor’s Office nor the Judiciary has managed to dispel the shadow of impunity that hangs over this case.

The hearing against those accused of the crime was postponed from June 3rd until it was finally held on August 28th, because the prosecution responded late to the request for a plea bargain by the accused Oscar Alexis Guardado, who is accused of firing the weapon at the defense attorney. Meetings to continue pursuing the lines of investigation continued in the following months.

This December 5th, the Municipal Committee in Defense of Common and Public Goods of Tocoa reported that, for the seventh time, the hearing to present evidence in the case of the defender’s murder was suspended. They indicated that this hearing is a crucial step toward a public trial to determine how the criminal organization that carried out the murder operated.

In this regard, the Observatory for Justice of the Defenders of the Guapinol River pointed out that, almost a decade after attacks against the Committee of Common and Public Goods of Tocoa, and despite the precautionary measures granted by the IACHR, the Honduran State has not deployed an effective strategy to investigate, prosecute, and dismantle the criminal networks behind these events.

Therefore, they demanded that the Judiciary guarantee prompt, diligent, and fair trials that include the full truth about the crime: planning, financing, and protection networks; the prosecution of all those responsible, including the masterminds who remain free and threaten those who defend their land; and an end to the delaying tactics that block a transparent trial with real guarantees.

In April, the National Assembly of the Ortega-Murillo regime approved the Law on Environmental Conservation and Sustainable Development Areas this legislation, according to environmentalists, prioritizes the economic interests of the regime’s elites and associates over the country’s protected natural resources. This is due to changes such as referring to the «exploitation» of resources instead of their «protection.»

Article 1, which outlines the law’s general objective, speaks of harmonizing the criteria and categories of protected areas with «rational use,» «transforming the path of economic growth.» Article 21 specifies what is permitted within protected areas: economic activities, exploitation of geothermal, geological, mineral, and hydrocarbon resources, among others. It also opens the door to «subsistence» hunting, the construction of hydrocarbon and hydraulic infrastructure, and aquaculture concessions.

This law connects with the complaints of La Fundación del Rio regarding mining activity in ecological reserve areas. The Fundación del Río (Foundation of the River) stated on its social media that “Since 2019, the Fundación del Río has identified four illegal mining sites in the Indio Maíz Reserve and three within the Rama Kriol territory. Las Cruces is the largest: 250 hectares (equivalent to about 350 soccer fields), three neighborhoods, 724 shacks, two bars, a church, and areas known for prostitution and drug trafficking.”

Furthermore, they denounced that between 2023 and 2025, the Nicaraguan Army (EN), particularly the Southern Military Detachment, has published 22 information notes on various arrests and seizures of materials, equipment, and supplies dedicated to mining activity within the Indio Maíz Biological Reserve.

“In these notes, the EN confirms the mining activity; however, its actions have been concentrated on the San Juan River, particularly at the Boca de San Carlos post; other institutions such as MARENA and the Ministry of Energy and Mines have not officially confirmed the mining activities in the area,” they point out.

Furthermore, this year, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) is publishing its report on “Violence against indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples of the Caribbean Coast in Nicaragua”, which analyzes the situation of violence faced by these peoples and its impact on human rights.

The IACHR identifies a series of patterns of violence perpetrated against these communities, including: armed attacks carried out by settlers and organized crime with the state’s tolerance; assassinations and the criminalization of traditional authorities, community leaders, and land defenders; threats, harassment, and extortion of communities; as well as acts of torture and sexual violence. “These acts of violence occur under structural impunity and in a context of absolute concentration of power in the executive branch,” the report states.

The physical and cultural existence of Indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples is at risk. “The violence perpetrated by armed settlers has resulted in the dispossession and displacement from their ancestral lands and territories, threatening their cultural and collective survival. These territories not only constitute their living space, but are also the essential basis for the development of their knowledge, ways of life, traditions, and spirituality, as well as for the continuity of their worldview. In this sense, territorial dispossession and forced displacement violate the right to cultural identity and collective ownership of these peoples,” the report concludes.

The other side of the so-called “green country” – the narrative that has positioned Costa Rica as a protector of nature – is revealed in light of the stories of land defenders who have been murdered and threatened in a country that does not recognize their work or adhere to commitments to environmental rights through international agreements such as the Escazú Agreement, which commits States to their comprehensive protection.

On August 10, Pablo Sibar, a 69-year-old Indigenous leader from Térraba, was threatened on his own land by people who had invaded his property. The police refused to evict them because they, like Sibar, also possessed a certificate from the Térraba Integral Development Association (ADI). This system, established in 1979 under the Indigenous Law, outlines the process for transferring and negotiating Indigenous lands among members of these communities.

However, outsiders arrive unannounced in the communities, carrying certificates issued by the ADI claiming ownership of the land. For social organizations and activists, these actions reveal a pattern of dispossession, harassment, and violence against Indigenous territories. Some of these conflicts have culminated in the murders of Jhery Rivera and Sergio Rojas, Indigenous leaders whose crimes remain unpunished.

On the cusp of 2026, Central America stands as a wounded land, where the impacts of climate change, mining, and megaprojects have torn at the fragile skin of the earth, met with indifference from states that continue to turn their backs on environmental issues. Land defenders are silenced with bullets and malicious legal proceedings amidst democratic backsliding that imposes control and censorship in the face of the desperate cry of the land and the communities demanding dignified living conditions and the protection of nature.

But this assessment is not an epitaph. Small victories like the freedom of Alejandro, José Ángel, and the five from Santa Marta offer hope and a cry of rebellion against the indiscriminate handover of land and human rights violations. It is time to sow the seeds of resistance.

“Our consciences will be shaken by the fact that we are merely witnessing self-destruction based on capitalist, racist, and patriarchal predation.”

Berta Cáceres

| Cookie | Duración | Descripción |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |